In a recent Sydney Morning Herald article , Ed Santow, former Australian human rights commissioner and co-founder of the Human Technology Institute, suggested that public authorities carry a heavier responsibility than the corporate sector in their use of AI because “citizens are receiving decisions [from Government AI] that are life changing in the corporate sector, people generally can shop elsewhere [but] Government is the only game in town”.

Right on cue, the European Law Institute has released ‘oven ready’ model rules specifically designed for public authorities using AI, developed by an impressive project team comprising judges, legal academics, technologists, practicing lawyers and bureaucrats.

Scope of the model rules

While the model rules reference the EU’s AI Act, they are broader in three ways:

the model rules are designed to be adopted in both EU and non-EU jurisdictions, and therefore are drafted on a standalone basis, with scope for adaptation to local law and for local political decisions about the priorities in protecting citizens;

the model rules apply broadly to any algorithmic decision making system (ADMS), defined as ‘a computational process, including one derived from machine learning, statistics, or other data processing or artificial intelligence techniques, that makes a decision, or supports human decision-making used by a public authority.’ The Project Team commented that while the EU AI Act uses the term ‘artificial intelligence’, they preferred a broader and more technology neutral term because ‘[w]hether or not an ADMS uses AI technology is often disputable and more conventional algorithmic systems can also pose relevant risks.’

the ‘decisions’ made by ADMS to which the model rules applies is much broader than ‘decisions’ in an administrative law sense of binding legal determinations. The

Project Team considered that, given the far reaching social, political and equity implications of a government’s use of ADMS, the model rules should cover ADMS used to make non-legally binding determinations, such as the giving of warnings or advice, or as input in developing new or changed policies (e.g. to establish surveillance cameras in a certain area where an algorithmic system has detected an increase in crime).

Determining the risk profile of ADMS

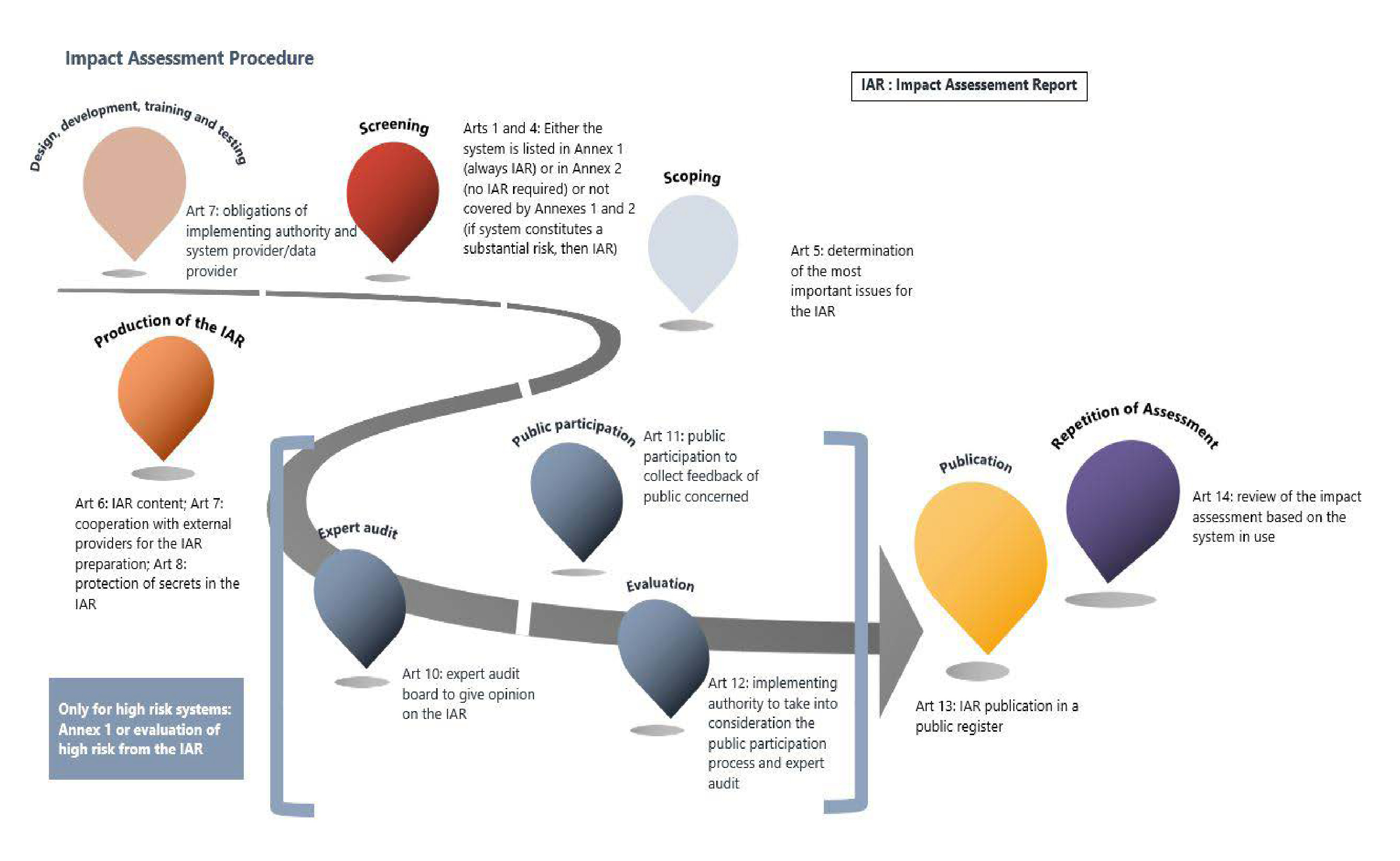

The model rules require an upfront risk analysis of all ADMS and then a more intensive process for AI identified to be ‘high risk’. The end to end process is depicted below.

High risk ADMS are identified in one of two ways:

‘always high risk’: the adopting Government can set out a ‘laundry list’ of high risk AI in schedule 1 of the model rules. The Project Team suggests starting with the list of high risk AI in the EU AI Act, which includes any facial recognition systems, systems determining eligibility for social security, or for predictive policing. However, going back to the theme of the special responsibility of governments in using algorithmic tools, the Project Team also suggests that the ‘always high risk’ include ADMS used in critical infrastructures, such as rail and air traffic, telecommunication networks and other digital infrastructure, ADMS used by tax authorities, or authorities in the fields of environmental or economic law.

case by case assessment: this assessment is made by the agency proposing to adopt ADMS (called the implementing authority) using a detailed questionnaire set out in Annexes 2 and 3 of the model rules which draws heavily on the Canadian AI risk assessment tool. This screening tool is fairly readily applied: most of the questions are multiple choice questions; each answer should be assigned a certain risk value; and the sum of all answers yields a risk score which determines the risk level. For example:

Is the impact resulting from the decision reversible?

Yes, it is easily reversible. [risk value of 0]

It is likely to be reversible. [risk value of 1]

It is difficult to reverse. [risk value of 2]

It is irreversible. [risk value of 3 or higher]

Assessing the pros and cons of high risk ADMS

If the proposed ADMS is assessed to be high risk, the implementing authority is required to undertake a detailed upfront assessment process that typically will involve five steps.

The first step is the implementing authority undertaking a scoping study to identify the most important issues and the necessary level of detail of the impact assessment. While not mandatory, this allows the implementing authority to identify which of the extensive list of matters identified in the model rules as potentially being within an impact assessment are most relevant to the particular ADMS being reviewed. But the Project Team cautioned, maybe with an eye to how bureaucracies can sometimes work, that the scoping study is “only about setting priorities, not about excluding from the impact assessment aspects mentioned.”

The second step is the implementing authority undertaking an impact assessment study of the proposed ADMS. The matters which the model rules specify for an impact assessment are fairly standard for such studies, but with a ‘spin’ that recognises the public mission of the implementing agency: for example:

an assessment of the performance, effectiveness and efficiency of the system with regard to the public objectives as defined in the applicable law, in particular whether the performance of the system might be flawed by low quality data during its use.

an assessment of the specific and systemic impact of the system on democracy, societal and environmental well-being.

an assessment of the impact of the system on the administrative authority itself, in particular the estimated acceptance of the system and its decisions by the staff, the risks of over- or under-reliance on the system by the staff, the level of digital literacy, and specific technical skills within the authority.

a reasoned statement on the legality of the use of the system under the data protection law, administrative procedure law and the implementing authority’s governing law.

The Project Team called out that, in contrast with other impact assessment studies, the model rules requires that not only the risks be considered but also how to maximise the public and administrative benefits of ADMS:

the problem [is] that public debates on AI and some other impact assessment models often concentrate on risk alone. This threatens to neglect the potential of ADMSs to improve the work of public administration. But it also aims to avoid exaggerated optimism: some public authorities adopt ADMSs uncritically without assessing their functionality. This might lead to disappointing results and a waste of (financial) resources. Thus, it is important to specify and investigate carefully the potential benefits of the system and the requirements for achieving them (e.g. system architecture, accessibility for the public, comprehensiveness and quality of the data, etc).

The impact assessment must be undertaken by the implementing authority itself - and cannot be outsourced, even where the ADMS is being developed externally or is an ‘off the shelf’ solution supplied by Big Tech. That said, the model rules recognise that the implementing authority may need to work closely with an external developer to undertake the impact assessment. However, detailed, discoverable records of the dealings between the external developer and the implementing authority need to be kept for the reason that, as well as proving the fulfilment of obligations, this will facilitate determining the cause (and the body liable) should the system stop performing as intended due to technical bug, human error, bias in datasets, etc.

Transparency requires that the impact assessment report be comprehensive, and that it be accurate and understandable to the public. The Project Team recognised that there can be “a potential discord between legal protection of broadly understood secrets and transparency of the impact assessment and general principle of transparency of public administration.” This means that a developer will need to accept that, when dealing with a public authority, “the protected secrets are not of an absolute nature”, but rather may need to give way to some extent to the right of citizens to understand the ADMS used by governments to make decisions affecting them.

The third step is review of the impact assessment report by an expert panel. The expert panel is to be composed of more than ‘tech heads’, but needs a diverse skill set, including technological, commercial, business, political, and legal skills relevant to the use of algorithmic decision-making systems in public administration, and also a diversity of human experience, including age, gender, vocation and socio-economic class.

As well as reviewing the report for compliance with the model rules, the expert panel is to be given access to ADMS, including the system’s source code and datasets used for training and testing purposes, and be able to use and test the system’s working in practice. The audit report can identify missing steps of the impact assessment process, deficiencies of the system design, development, training or testing, additional, unforeseen risks, insufficient measures to protect the public, or additional concerns, or recommendations to the implementing authority.

The fourth step is an opportunity for the public to comment on the ADMS. To enable effective consultation, the implementing authority is to publicly release the impact assessment report and the audit report.

The final step - or rather an overriding consideration that applies throughout this process - is that the implementing authority is to consider the ‘proportionality’ of using ADMS. The Project Team states that the “impact assessment is not a licensing procedure[i]t results in a report and not a licence.” The implementing authority needs to stand back and decide whether algorithmic decision making over other (more human) processes will better address the implementing authority’s objectives and satisfy the public good. The Project Team, probably in an effort to keep the ‘revenue hounds’ in treasury and finance ministries in check, made a deliberate decision to use the term ‘proportionality’ over ‘cost benefit analysis’ because the latter term ‘might imply an overly narrow focus on (economic) effectiveness, while the Project Team would like to encourage a more holistic view that takes societal interests and individual rights into account.’

No ‘set and forget’

Once the ADMS is operational, the implementing authority is required to go through a version of the above process (including expert panel audit) to regularly monitor the ADMS:

whenever there are factual indications of substantial negative impact on the impact assessment criteria in the model rules; and

even if everything seems to be OK, after the first 6 months of operation and thereafter every two years.

These periodic reports have to be published, so there is no chance of cover-up.

New specialist ADMS agency

The model rules call for a specialist independent authority to oversee decisions by individual government agencies to implement ADMS. The supervising authority could be a new agency or the role of an existing agency could be expanded, such as the data protection or privacy authority.

The supervisory authority cannot reverse the decision of an individual agency to adopt ADMS, but the model rules provide for the following specific roles:

the implementing agency has to provide a copy of the screening report, impact assessment report, the audit report and its response to the audit report and public consultations to the supervisory authority which, if it considers there have been mistakes or errors, can require the implementing authority to reconsider.

the supervisory authority appoints the expert audit panel, and for this purpose maintains a list of potential candidates.

the implementing authority can ask for advice on the scoping study.

affected parties can ‘appeal’ the implementing authority’s decision to proceed with the ADMS, but again that remedy is to remit the decision to the implementing authority to reconsider. The model rules expressly recognise that non-governmental agencies have standing to appeal.

if the supervisory authority has reason to think the ADMS has gone off the rails in the course of its operational life, such as through self-learning, the supervisory authority can initiate its own review and can recommend that ADMS be suspended. The Project Team note that alternatively this power could be crafted to be mandatory or the supervisory authority could seek a court order to stop use of the ADMS.

In addition to these specific roles, the supervisory authority is to function as a knowledge centre that informs and advises public authorities, affected individuals and organisations and the public on all issues related to the use of systems by public authorities.

Peter Waters

Consultant