The UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) recently released a detailed market study of the music streaming business.

Streaming came along in the nick of time

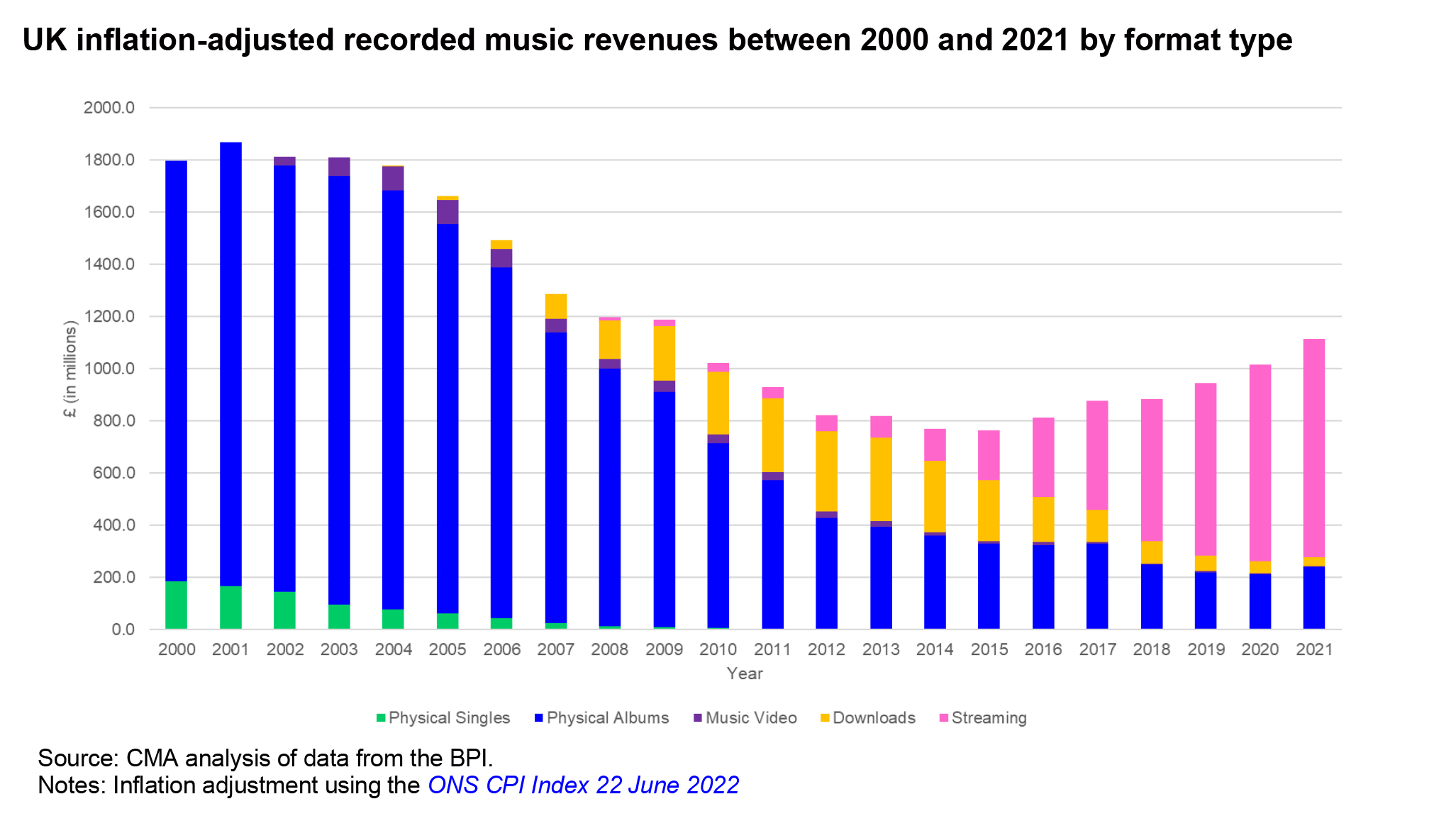

The recorded music business collapsed in the early days of the internet because piracy became a common consumer habit. Between 2001 and 2015, UK recorded music revenues dropped around 60%. Online music stores (e.g. Apple Music) had some limited success in reversing the decline by allowing consumers to purchase individual tracks or albums that they owned and could listen to when they liked. But streaming music services were a game-changer, the first being Spotify in 2008.

The following graph shows how music streaming saved the music industry.

Who uses streaming music services?

The proportion of people in the UK accessing music through streaming music services has grown from 16% in 2015, to 23% in 2017 and to 45% in 2021.

As would be expected, usage of streaming music varies by age group. Of users aged 16 to 34, around 4 in 10 listen to a streaming service several times a day: four times higher than for users aged 55 and over.

It looks like streaming music will be ‘who killed the radio star’. While radio still remains the most common form of listening in the UK, there is a clear shift to streaming music: weekly reach for listening to live radio fell from 83% of adults in 2015 to 63% in 2021, while streamed music rose from 16% to 45%.

What do we listen to?

The defining feature of music streaming services is their ‘full catalogue’ of music. You can listen to almost the entire history of recorded music. Most major streaming services offer catalogues with more than 75 million tracks. Around 60,000 new tracks are added to Spotify every single day.

But listening habits are remarkably narrow. Music older than 12 months (the so-called ‘back catalogue’) represents a very high proportion of streams, rising from 76% in 2017 to 86% in 2021. Hence the huge amounts being paid for back catalogues – the Boss sold his for US$550 million.

While the streaming services are using increasingly sophisticated algorithms to ‘choose music for you’, most of us prefer to choose our own. 42% of streams are from user-created playlists whereas only around 20% of streams are from playlists provided by the music streaming service.

Streaming music providers

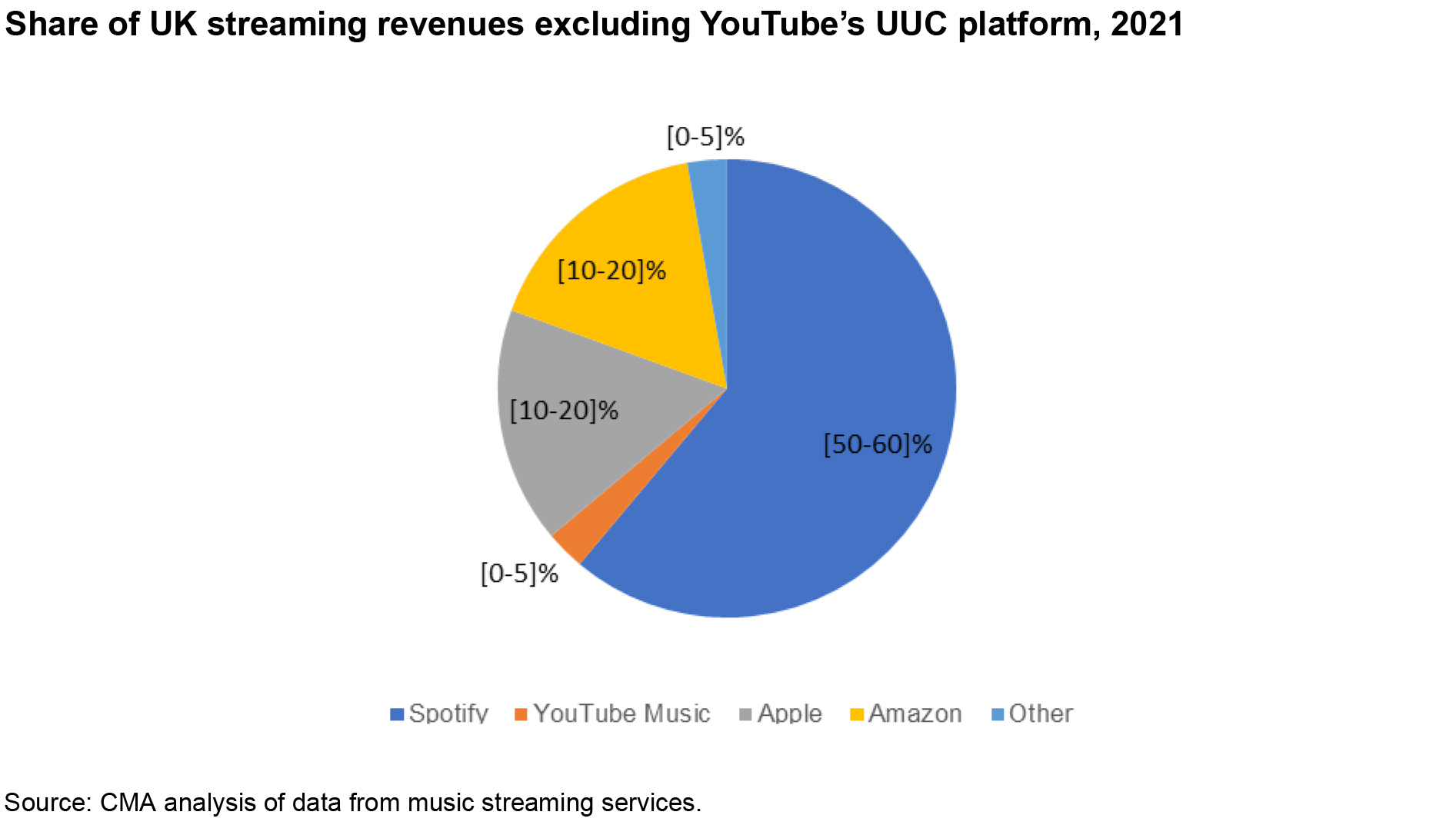

Spotify is the market leader in the UK, although its market share has dropped from 80-90% in 2015, losing share to Apple and Amazon.

The CMA noted that User Uploaded Content (UCC) platforms, such as YouTube, are important means by which consumers discover music, but the CMA does not consider they competitively constrain the commercial streaming services. UUC platforms make music available for free because they generate revenue from ads. The UUC platforms often have a ‘safe harbour’ under national copyright laws (including in the UK) that limit their liability for illegal content uploaded by its users in certain circumstances, which means unlike the commercial streaming services, they do not have to negotiate with rights holders. However, the UUC platforms do not have the ‘full catalogue’ of music.

The More Things Change, The More They Remain The Same

The CMA identified five ways in which an artist can get their music ‘out there’:

- sign with a major label, such as Sony, Universal and Warner. The majors provide a full range of services called ‘artist and repertoire’ (A&R) which relate to the discovery, signing and development of artists, as well as the recording of their music, funding, and organising tour support. These deals typically involve an upfront advance and the artist assigning their copyright.

- sign with a smaller, ‘independent’ (or ‘indie’) label, such as Beggars Group, BMG Rights Management, which also can involve A&R services but increasingly on a ‘menu’ approach;

- use an ‘artist services’ provider, such as Believe, PIAS and Empire. These tend to provide a scaled down version of ‘A&R’ services called ‘artist and label’ (A&L) services, have smaller upfront payments and no assignment of copyright;

- choose to distribute their music as a self-releasing artist using an established platform known as ‘DIY’ platforms, for example TuneCore, Sistroid. DIY providers also offer low touch (tech-driven) marketing and promotion services. All revenues earned go to the artist, with the DIY provider charging a fixed fee (on an annual or monthly basis) for their services; or

- secure the services of a manager and team for various levels of promotion and other support and arrange distribution via a ‘label services’ provider.

However, what is remarkable is that the market position of the major labels remains largely intact - despite having to survive the revenue chasm outlined above. The CMA commented:

“In terms of their share (by volume) of total UK streams, the majors accounted for over 70% in 2021 – a similar proportion as in 2015. Their music dominates the popular charts. The combination of the rights they hold in recordings along with the rights they hold in publishing, means that in 2021 they collectively had some form of rights in 98% of the top one thousand singles.”

If anything, their control of back catalogues anchors their power in the new world of streaming.

But the business models have been transformed

An obvious change in the value chain is the avoided costs of producing the physical media – 1s and 0s are much cheaper than pressing vinyl or CDs.

But there are two other features of the streaming music business model which have been more transformative in the upstream value chain.

First, in the world of physical media, the revenue generation was through one-off sales: how often a track or album was listened to after it had been purchased had no impact on revenues. But with streaming, revenues and royalties can be earned over a much longer period of time: music that is listened to repeatedly will be rewarded accordingly.

Second, the ongoing payment is not per stream but a flat “all you can eat” subscription fee. The CMA also noted that the headline subscription fee for music streaming had been remarkably stable for years. This means that with more artists and more streams being played, the average value of each stream and the average earnings per artist fall. As such, thousands or even millions of streams are now commonplace.

The CMA calculated that a million streams per month will only earn an artist around £12,000 a year.

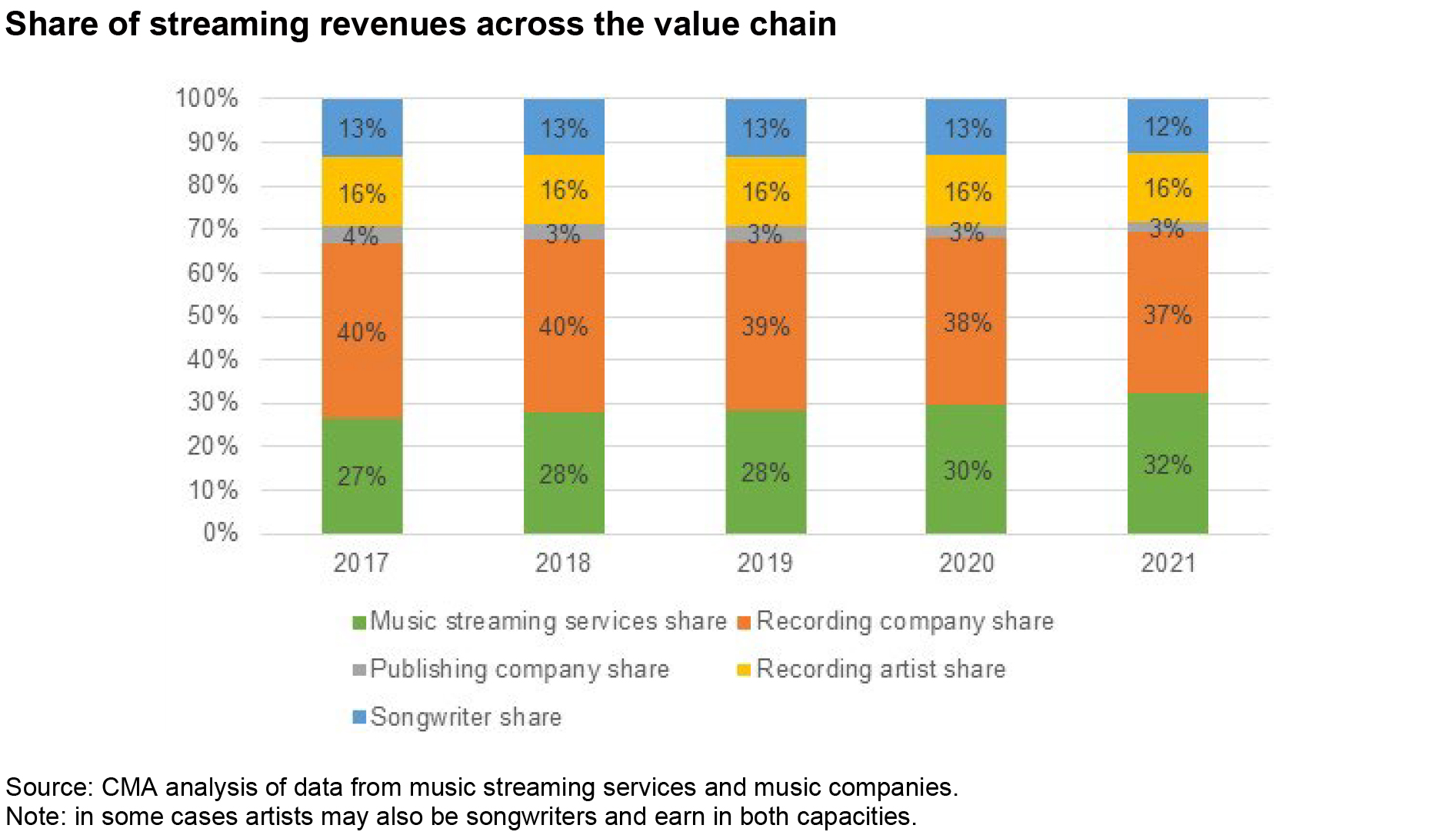

As the following graph shows, as the streaming services have grown in scale, their share of revenue has grown at the expense of the record companies. But the share of song writers and artists has remained much the same.

Competition assessment

Major labels vs streaming services

The CMA found weak competition between the major labels to supply content to streaming companies, and that streaming services had limited leverage against the major labels– all because the ‘full catalogue’ demanded by consumers meant the streaming services had no choice but to acquire content from all the major labels.

As the streaming services have increased in scale, there is a growing interdependence between the streaming services and the major labels. However, the CMA notes that “this increasing mutual dependence does not necessarily result in equal bargaining power of the music streaming services and record companies.”

But the CMA also found that, notwithstanding their high and persistent level of control of music content, “the record companies do not appear to be earning sustained and substantial excess profits.”

Competition between streaming services

The full catalogue business model means that the streaming services cannot compete against each other on content. Instead, streaming services seek to differentiate themselves in other ways, including through their playlists, user functionality, and features such as audio quality or additional content such as podcasts (Joe Rogan’s US$200 million deal with Spotify).

The CMA found there were barriers to churn between streaming services. Again, because many of us prefer to build our own playlists, ‘porting’ that playlist to a different service can be tricky. There are portability services such as Soundiiz, but consumers have a low awareness of them.

However, the CMA did not think these switching barriers were problem for competition between streaming companies, for three reasons.

First, consumer tended to exercise choice by ‘multi-homing’ (i.e. subscribing to more than one service):

“If consumers of one service believed that they are not getting a competitive offer and were considering switching, there are regular free trials, as well as ad-funded tiers, to enable them to try out different services. Paid subscriptions are typically on a month-by-month basis.”

Second, the main competitive background was still for new customers.

Third, the streaming companies, in which may come as a surprise to many, are not necessarily highly profitable. Spotify historically has not been profitable and, based on its statutory filings, had a 1% operating margin across its entire business in 2021.

Major labels vs Indie

The CMA recognised that the major labels have strong advantages over the indie labels:

“The majors have significant advantages linked to their scale that are difficult for independent record companies to replicate. Most notably the majors’ ownership and earnings of large back catalogues of music for which they have long-term rights gives the majors significant financial advantages. Back catalogues are responsible for over 80% (in 2021) of music streams and therefore account for a high proportion of streaming revenues.”

Yet there are also some countervailing factors. Because most users prefer to build and listen to their own catalogue, this limits the extent to which the majors’ influence of music streaming playlists can act as a barrier to expansion of independent record companies.

What about the artists?

The digitalisation of music has lowered ‘barriers to entry’ for musicians and songwriters. However, as the CMA noted, few succeed in this crowded field:

“The data shows a large increase in the number of low and mid-range artists under streaming. However, in terms of share of streams the market remains heavily dominated by the few high-range artists who become successful, many of whom are generally contracted to the major labels. Research commissioned by the [Intellectual Property Office] found that between 2014 and 2020 the top 1% of artists accounted for 78–80% of streams, and the top 10% for 98%.”

While there is the opportunity for artists to by-pass traditional music companies and upload their music directly to streaming services, most artists continue to sign with a label. The CMA noted that the major labels have the marketing and production skills, the global reach and the industry relationships to bring to bear to help artists break through. In many ways, the major labels count for more beyond the streaming services because live performances, at least prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, were the greatest source of income for artists. Streaming, despite being the biggest contributor to global recorded music revenues, on average, accounts for only 6% of an artist’s music-related income. The heft of a record label is needed to pull together a live performance tour.

The CMA recognised that the bargaining position of artists with record labels was weak. George Michael famously lost a court case challenging the record deal he signed with Sony as a young man.

But the CMA considered that the artists’ weak bargaining position reflected the risks the record companies faced in signing artists: Approximately only one in ten investments made by record labels breaks even on the upfront label investment. It is common for new artists to receive only one offer (if any) to sign a traditional record deal from a major or indie label.

But the CMA did not think breaking the power of the major labels would help artists much:

“Our current view is that there is unlikely to be scope to improve outcomes for artists in a material way through greater competition, for example through a less concentrated market structure, reducing barriers to expansion, changing licensing terms over the placements of the majors’ music or changes to the information presented to artists. The lack of substantial and sustained excess profits of the majors suggests that there is little prospect for greater competition to significantly improve outcomes for artists overall.”

Conclusion

The CMA decided not to undertake a full scale market investigation:

“our judgement is that we currently do not have reasonable grounds to suspect.. specific features [of the music streaming business] could be restricting or distorting competition in the UK….On the contrary, prices for consumers are dropping in real terms, consumers have easy access to large catalogues of music covering a vast array of genres and time periods for a fixed monthly price (or free, but with ads), and overall, consumer satisfaction with music streaming services is high.”

Read more: CMA shines a light on music streaming

Visit Smart Counsel