The Pew Research Center recently surveyed 25,000 adults across 19 advanced economies in North America, Europe, the Middle East and the Asia-Pacific region on their views of the impact of social media on democracy in their country. A median of 57% say social media is more of a good thing for their democracy, with 35% saying its a bad thing. But there were substantial national differences: the US was an outlier, with just 34% of Americans thinking social media is good for democracy, while 64% saying it had a bad impact, and with Australians effectively split.

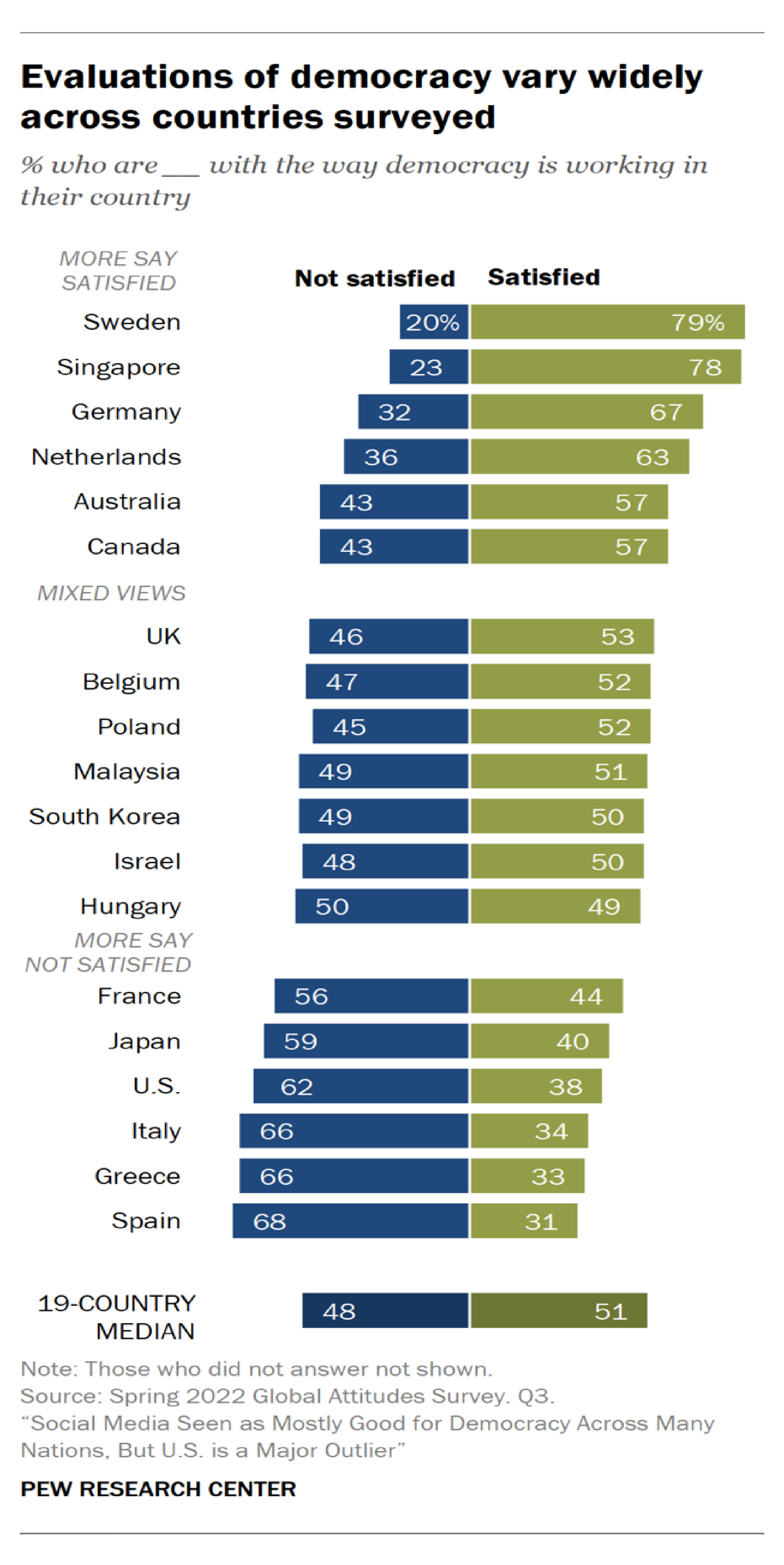

Do you think your democracy works?

Pew started with a baseline evaluation of citizens’ satisfaction with democracy in the surveyed countries. A median of 51% reported they were satisfied with how democracy was working, but again with big cross-national differences. Sweden (79%) and Singapore (78%), which might be considered to have very different operational models of democracy, came out as most satisfied. Australia also reported a heathy majority satisfied (57%), with Pew noting the recent change in Federal Government.

Mixed views were reported in the UK, Israel, Malaysia and South Korea, whilst countries such as France (56%) and the US (62%) had majorities expressing dissatisfaction with democracy in their country.

Pew also looked at citizens’ perceptions of their capacity to influence politics, and found that a majority in 18 of the 19 countries surveyed said that their political system does not allow people like them to have an influence on politics. This included 71% of Australians would felt ‘powerless’, a similar level to the US (71%) and Japan (72%).

The only country where a majority of citizens thought they could influence politics was Sweden (65%), strikingly more positive that the next highest, Israel where 48% of citizens believed they could influence politics.

Unsuprisingly, Pew found a strong correlation between citizens answering that they felt they could not influence politics, and also feeling dissatisfied with democracy in their country. To take the ‘worst case’, more than 6 in 10 Americans were dissatisfied with their democracy and 7 in 10 thought they could not influence politics.Yet perhaps oddly, Australians on the whole are happy with our democracy, despite over 7 in 10 considering they have little influence on politics.

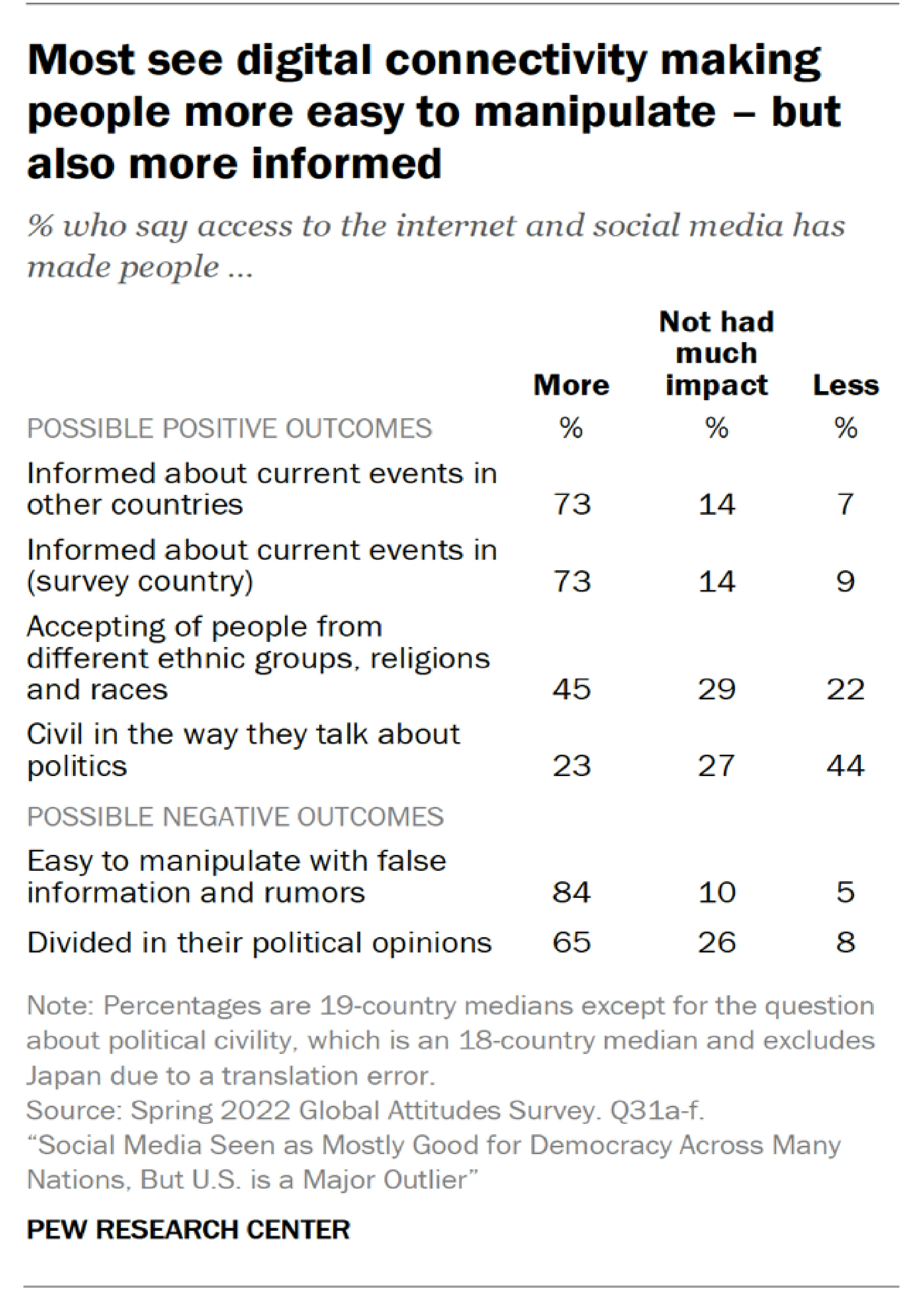

Social media leads to more informed citizens, but also misleads and manipulates them

Australia, along with most of the world, appears to be caught in a Catch-22 situation with social media. Whilst majorities in every country considered that the internet and social media has made people more informed, even more agreed with the proposition that it has made people easier to manipulate with false information.

Majorities in every country said that access to the internet and social media has led to people in their country being more informed about domestic current events. This number was highest in Sweden (85%), whilst Australia (76%) sat higher than the UK (73%) and much higher than the US (64%).

Equally, majorities across the 19 countries surveyed believed the internet and social media had made their country more informed about current international events, including over 79% of Australians, 76% of the British and 64% of Americans.

Younger adults tended to see social media making people more informed than older adults, who were more likely to describe social media as having little effect on information levels.

When it comes to misinformation, a median of 84% across the 19 surveyed countries thought that access to the internet and social media has made people more easy to manipulate with false information. Australians were amongst the most concerned about the negative impacts of social media, at 90% this response was the second highest out of all of the countries surveyed, only just behind the Netherlands (91%), and slightly above the UK (89%) and the US (85%).

These findings align with previous results published by Pew in August 2022, which found that a median of 70% across 19 countries surveyed classified the spread of false information online as a major threat (including 66% of Australians).

This may suggest a rise in individuals’ concerns about false information in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to a proliferation of misinformation campaigns that already intensified on social media before and during the Trump presidency.

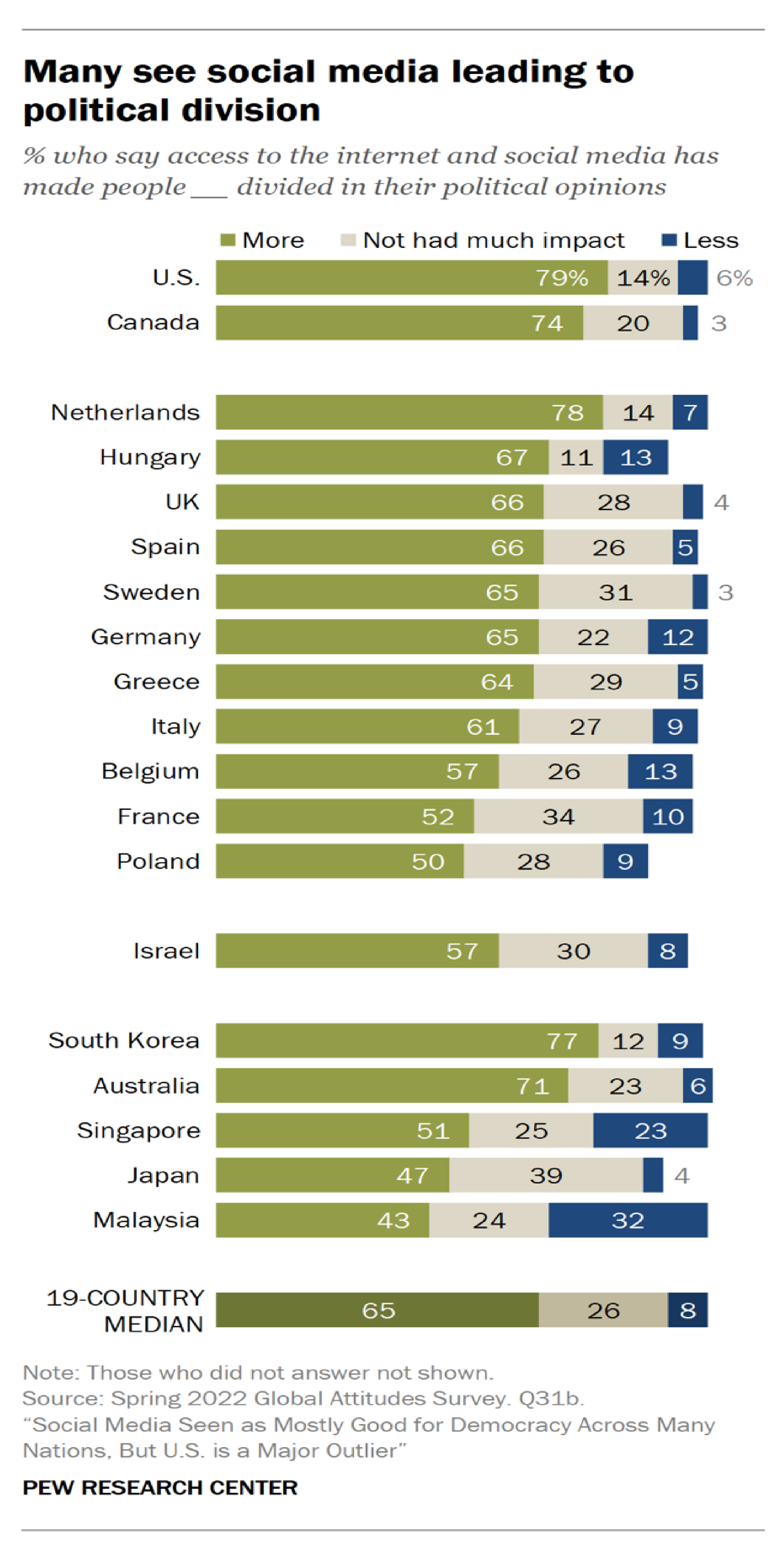

The ‘echo chamber’ effect

Majorities in the 19 surveyed countries surveyed responded that social media has made people more divided in their political opinions, with Japan and Malaysia the only exceptions. Concerns about political division were higher than the median in the US (79%) and the Netherlands (78%), with Australia not far behind at 71%.

Responses were similar when it came to considering social media’s effect on civility in political discussions. Whilst each country had less than half of responses saying social media had made people more civil, the degree of responses responding with “less” versus “little impact” was different across the countries. Australia’s responses corresponded mostly with the US, with sizeable majorities (over 61%) of the opinion that social media had increased hostility, and minorities (20% or lower) seeing little impact.

There is a little brighter picture on social media’s effect on tolerance. Australia’s responses mostly aligned with the 19-country median, with 45% saying social media has made people more accepting of people from different ethnic groups, religions and races, 26% saying the opposite, and 29% saying social media had not had much impact. However, South Korea (62%) was the only country with a clear majority saying social media had made people more tolerant, whilst Sweden had the largest proportion of citizens saying social media had had little impact (39%).

Younger people are more likely than older ones in most countries to say that social media has increased tolerance. In Australia, where 55% of adults under 30 say social media has contributed to people being more accepting of people from different ethnic groups, religions and races, compared with 37% of those ages 50 and older. This spread between younger and older Australians’ perceptions of the positive impact of social media (+18) is wider than in many other countries (e.g. Germany at +14 and the Netherlands at +11), but narrower than in the US (+23), which suggests that the US is polarised on this too.

Where does this leave us?

As more and more of our world integrates online, our dependence on the internet and social media for information will only continue to grow. This is especially relevant when it comes to the health of our democracy, given the growing influence of social media on our political views and exchanges with others about it. It is important that we trust these sources to tell us and others the truth, and provide civil spaces for open dialogue.

But while social media occupies a ‘global space’, the Pew survey shows a surprising difference in views between citizens in individual countries about the impact of social media on their body politic. These differences - both positive and negative - do not seem to be explained by geographic region, the degree of economic development, or even by Anglosphere vs non-Anglosphere countries.

At one of the spectrum, the Swedes are the ‘happiest democracy campers’: they believe their democracy works well, that by participating they can shift politics and that social media is a ‘democratising tool’, even with the caveats about misinformation risks. At the other end of the spectrum, US citizens appear to have lost faith in their democracy, to believe that its beyond their ability as individual citizens to change things, and that its social media that has poisoned the well.

Australians are at a somewhat strange place in the middle. We are almost as happy with our democracy as the Swedes, but are close to Americans in our scepticism of the usefulness of participating in democracy and even more fearful of social media’s negative impacts than them. Do Australians see a demarcation between citizens’ dealings on social media and the operations of government? Do we underestimate the impact of misinformation and polarisation on election outcomes and political movements? There is probably a politics PhD thesis in this!

Read more: Social Media Seen as Mostly Good for Democracy Across Many Nations, But U.S. is a Major Outlier