US legal researchers (Choi, Monahan and Schwarcz) recently completed the first randomised control study of “the effect of AI assistance on human legal analysis”. Other studies have focused on the ability of AI to undertake legal analysis on its own (i.e. substituting for a human lawyer’s judgment), whereas this study looked at AI as a tool for lawyers.

Methodology

The researchers randomly assigned 60 students at the University of Minnesota Law School to complete 4 separate legal tasks typifying the work of junior lawyers, drafting:

An originating court application for a fictional client alleging intentional interference with a business relationship and malicious prosecution.

A contract between a homeowner and a house painter. The material terms were provided, the contract was to be in plain English, no more than two pages, and completed within two hours.

A section of an employee handbook explaining employees’ rights under federal and state (Minnesota) law to take breaks to pump breastmilk for a child, which was to be no more than one page.

A client memo advising a fictional manufacturer whether it should place a warning label on a product when the product contains an allergen. The participants were provided four judgments and told not to do any other independent research.

Participants were required to keep accurate time records for each task. Their output was graded with a mark out of five by the researchers on an anonymous basis and without knowing whether the individual price of work involved use of AI.

Results

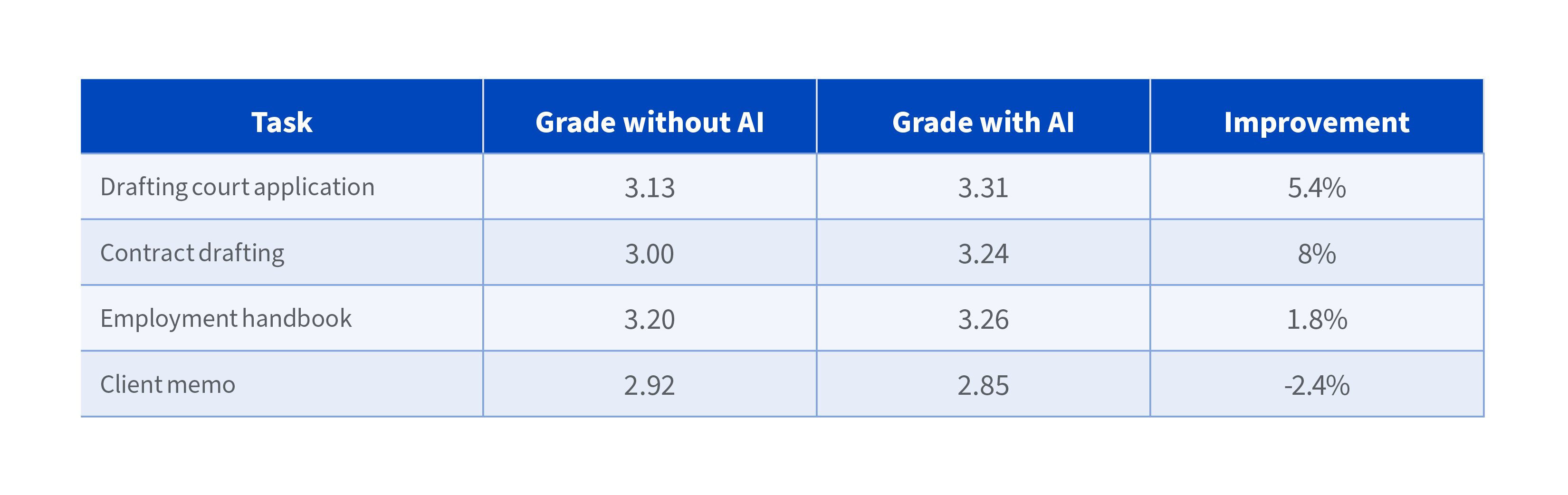

The researchers concluded overall, the use of AI resulted in little average improvement in quality, measured by the grades given by the human markers.

However, as the table below shows, there were differences between tasks, with AI helping the most on contract drafting (although still fairly modest) and resulting in a poorer performance on drafting the client memo.

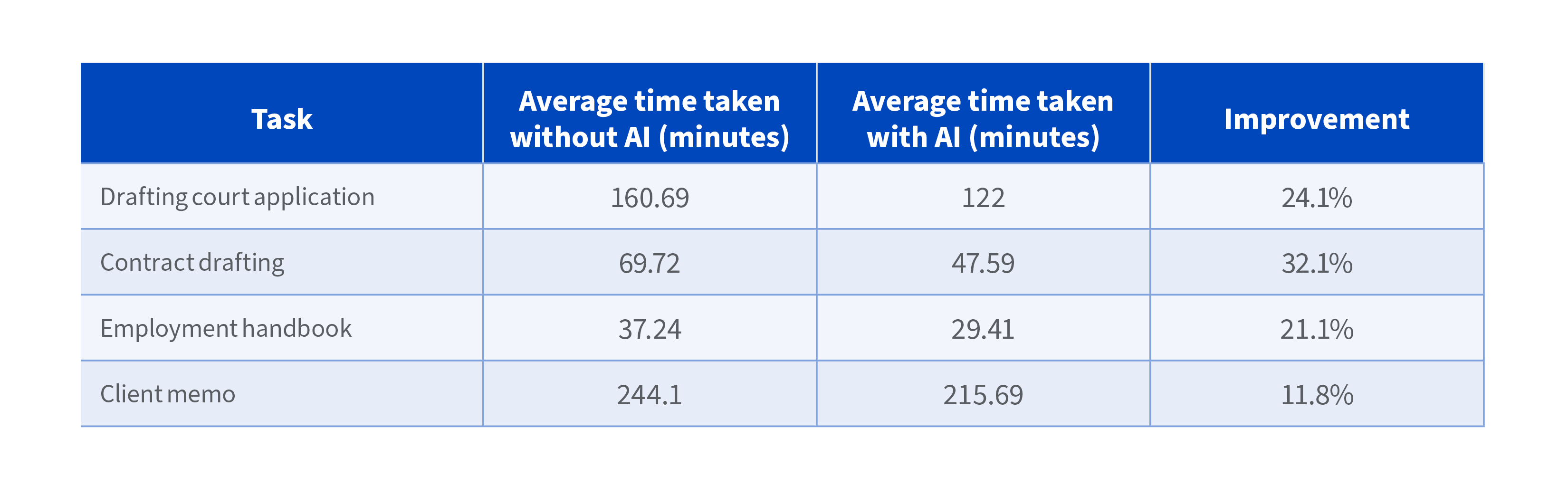

The results from using AI showed large and consistent decreases in the amount of time taken on each task, as the table below shows.

While speed of performance improved across all tasks, “the largest gain in speed (in percentage terms) occurs in the task for which GPT-4 was the most useful in terms of grade improvement (contract drafting), and the smallest gain in speed (again in percentage terms) occurs in the task for which GPT-4 was the least useful (client memo)”.

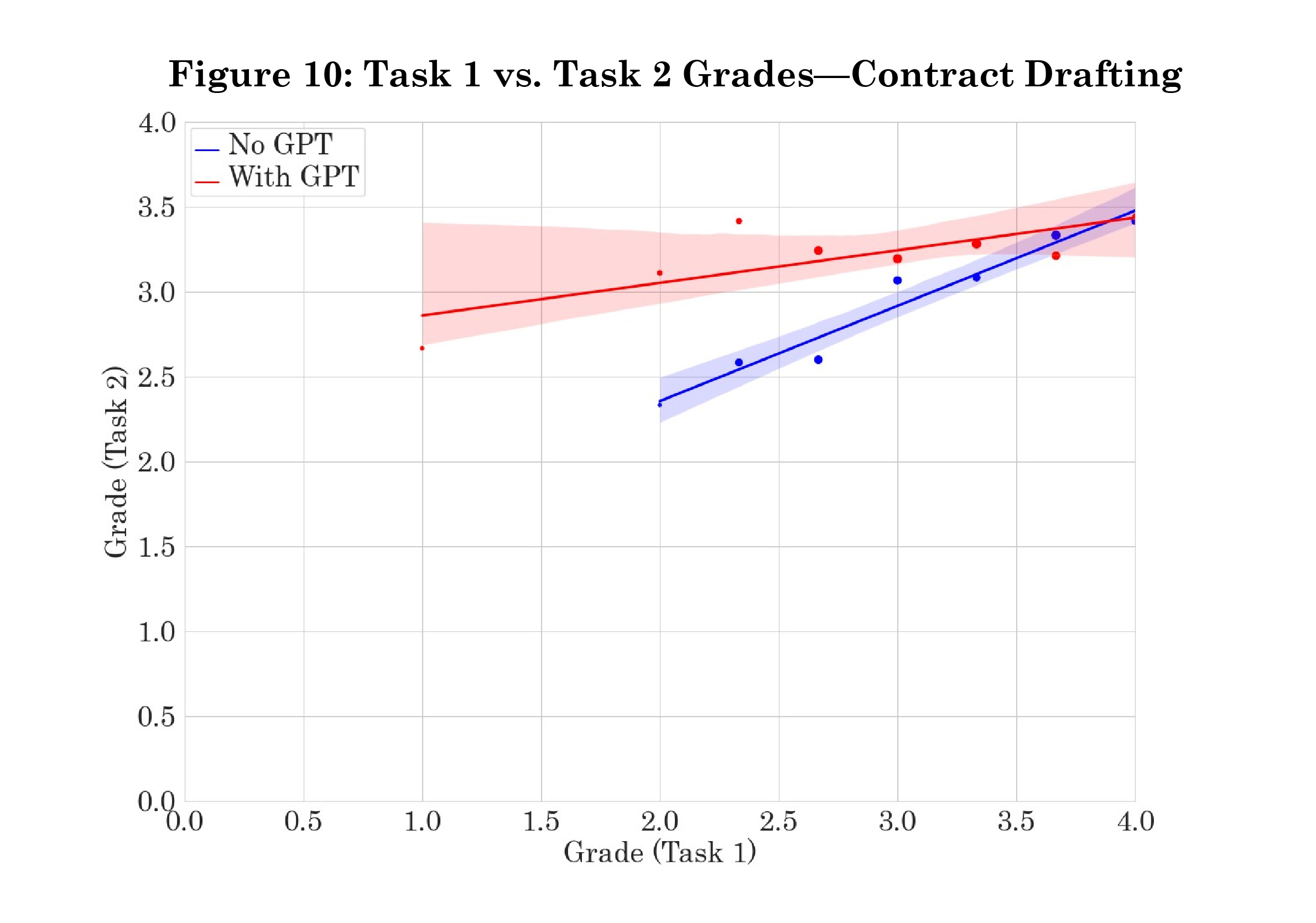

Other research into AI use in the workplace , such as call centres, has shown AI is of more assistance to poorer performing or less skilled workers. Because each participant performed two tasks with AI and two without, the researchers were able to compare how much AI helped each performer lift their grades compared to their grades without AI.

The graph below compares the marks of participants who used AI for contract drafting against the marks they got for another task which was human-only. The greater the gap between the lines, the greater the apparent performance uplift from AI. The graph shows participants with lower marks on human-only legal tasks improved their performance on contract drafting using AI much more than participants who were high performers already without AI.

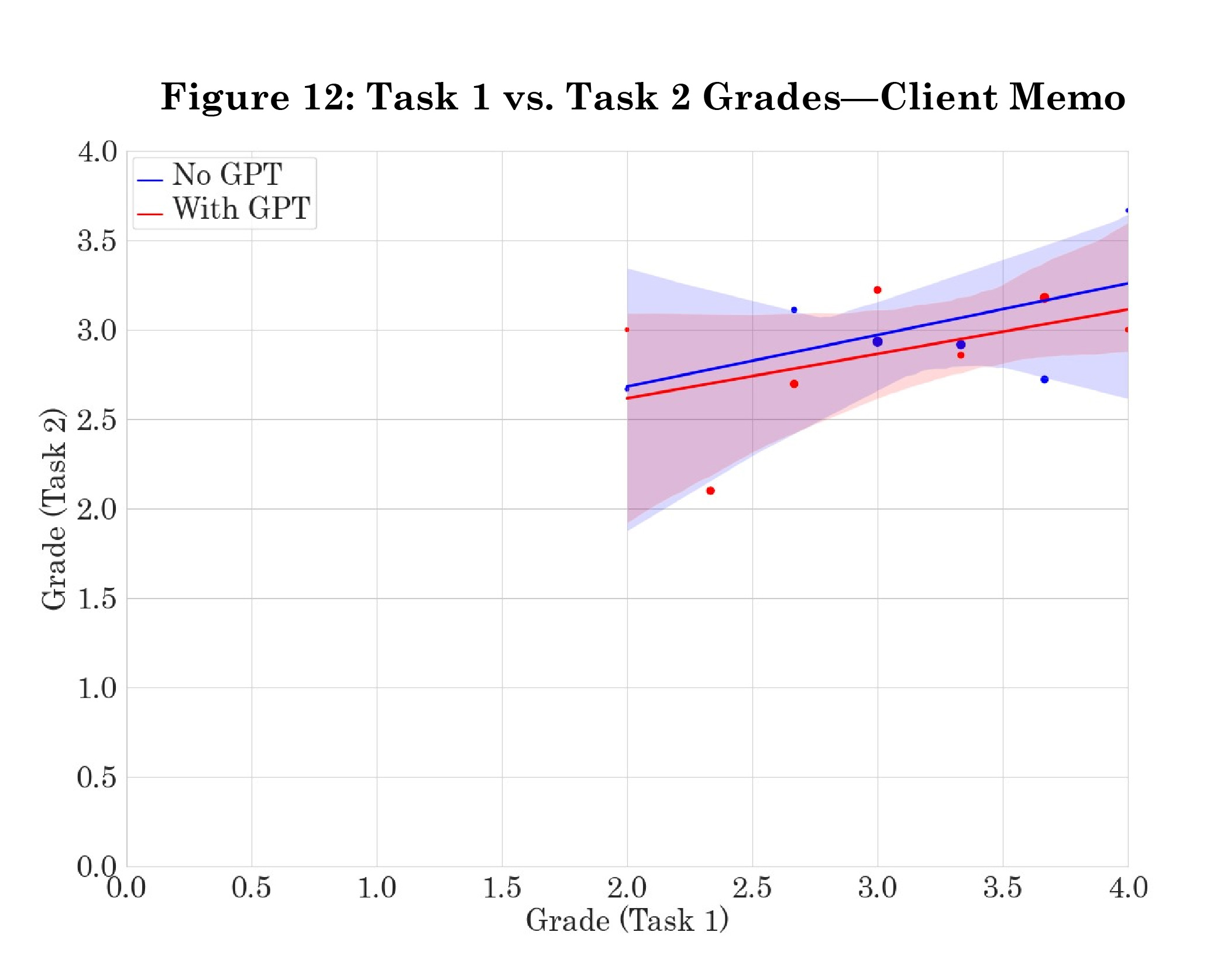

Even for poor performers, AI made very little difference in drafting the client advice, as the following figure shows.

The researchers looked at whether the impact AI had on speed of performance differed between the fast workers and the slower workers. Again, this was done by comparing the time taken by each participant on their AI-assisted tasks with the time taken on their human-only tasks. The researchers concluded GPT-4 has the potential to reduce time spent on tasks for lawyers of all ability levels.

In more qualitative results, the researchers found:

All participants, no matter on which tasks they used AI, reported a boost in task satisfaction, even where AI did not help them produce a materially better quality output than those who did not use AI for that task.

All participants also reported a boost in task satisfaction in using AI regardless of their skill levels. Again, this was the case both for lower skilled participants where AI made a real difference to the quality of their work product and for higher skilled participants where AI made no such difference.

Participants were also good at accurately identifying the tasks for which AI made an improvement in work quality (mainly contract drafting), even where the participants were amongst those who did not use AI for those tasks in the study.

What does this mean for legal practice?

The researchers conclude their study shows:

general purpose and widely available generative AI tools like GPT-4 and a limited amount of training can substantially improve the efficiency with which [junior lawyers] complete a broad array of legal tasks without adversely affecting (or even slightly improving) the quality of that work product.

We might have guessed that, but what is interesting about this study is it also shows lawyers can be trusted to identify when it is better to use their own brains and training than over-rely on AI.

But the researchers also cautioned law firms and practitioners to be alive to the uneven distribution of the benefits of AI across lawyers of different skill levels and across different types of legal tasks. While not posited by the researchers, the ‘levelling up’ in work product between lawyers might have implications for how law firms reward lawyers on individual performance when judging the quality of output is used as a proxy for the lawyer’s own skills.

On the uneven utility of AI for different legal tasks, the researchers commented:

The features of some lawyer tasks - such as negotiating complex deal terms or crafting high-stakes legal briefs - almost certainly make them less amenable to assistance from AI. Meanwhile, many other legal tasks are likely to be much more dramatically impacted by the availability of AI than those that we focused on in our experimental setting. While the research that young lawyers are pretty good at judging ‘horses for courses’, the legal practice needs to be discriminating in its AI deployment within the practice.

What does this mean for clients?

The researchers considered AI would be good news for commercial legal clients, in two ways.

First, in effect, clients should ask to share in some of the efficiency gains:

But rather than relying on market forces alone to decrease the cost of legal work product or increase the quality, we believe that our results suggest that clients should be proactive in asking their attorneys how they make use of generative AI and what impact that has on the quality and cost of the resulting legal services.

Second, AI will help clients do more of the routine legal work inhouse: “[t]he efficiencies associated with generative AI are virtually certain to shift the calculations associated with this make-buy decision”.

The researchers proposed AI may not result in more expedited or lower cost litigation because the time and resources freed up by AI may be redirected at more gladiatorial activity between plaintiffs and defendants in their slugfest.

What does this mean for legal education?

The researchers were sceptical of fears use of AI would be the death of legal reasoning by human lawyers:

...effectively using AI to craft legal arguments requires many of the same basic legal and analytical skills as other forms of lawyering, including a capacity to question initial answers, confirm the accuracy of arguments and sources, organize issues clearly, and assess the strength of alternative arguments.

To ensure the foundation of legal reasoning skills is laid down, the researchers argue use of AI by students should be banned by law schools in their first year courses. Conversely, in later year classes, law schools should actively incorporate AI training.

More information: Lawyering in the Age of Artificial Intelligence

Peter Waters

Consultant