Last week at its annual Worldwide Developers Conference, Apple announced the integration of AI into its phones and apps, including Siri. Apple says that:

Equipped with awareness of your personal context, the ability to take action in and across apps, and product knowledge about your devices’ features and settings, Siri will be able to assist you like never before.

But is this just the beginning of a much bigger world in which interactions are powered by AI assistants, including with each other (or more accurately, each other’s personal assistants)? A recent Google DeepMind paper on AI personal assistants says (a little ominously):

AI assistants could be an important source of practical help, creative stimulation and even, within appropriate bounds, emotional support or guidance for their users In other respects, this world could be much worse. It could be a world of heightened dependence on technology, loneliness and disorientation Which world we step into is, to a large degree, a product of the choices we make now. Yet, given the myriad of challenges and range of interlocking issues involved in creating beneficial AI assistants, we may also wonder how best to proceed.

What is an advanced AI personal assistant?

We have had personal assistants like Siri and Alexa which use natural language interfaces for a decade and large language models (LLMs) are the technology de jour, so how are the advanced AI personal assistants of the near-future so different from each other?

Personal assistants now use embedded AI, allowing users to speak natural language instructions that are interpreted through natural language processing. However, the DeepMind paper describes the current state of play as “a fragmented landscape... in which... the AI technologies are embedded as components of a wider software system... [and the] role of the AI is to complete a specific task as part of a predefined sequence of steps."

While LLMs are developing tremendous capabilities, they are designed to replicate the distribution of their training data to find the probability of ‘the next word’ given some textual context. They do not interact with or learn from their external environment ‘as they go’. While natural language processing means LLMs can listen to instructions from and respond conversationally to real world prompts, being able to operate within the real world requires the capacity to make decisions, execute tasks and react to the changing environment of the real world.

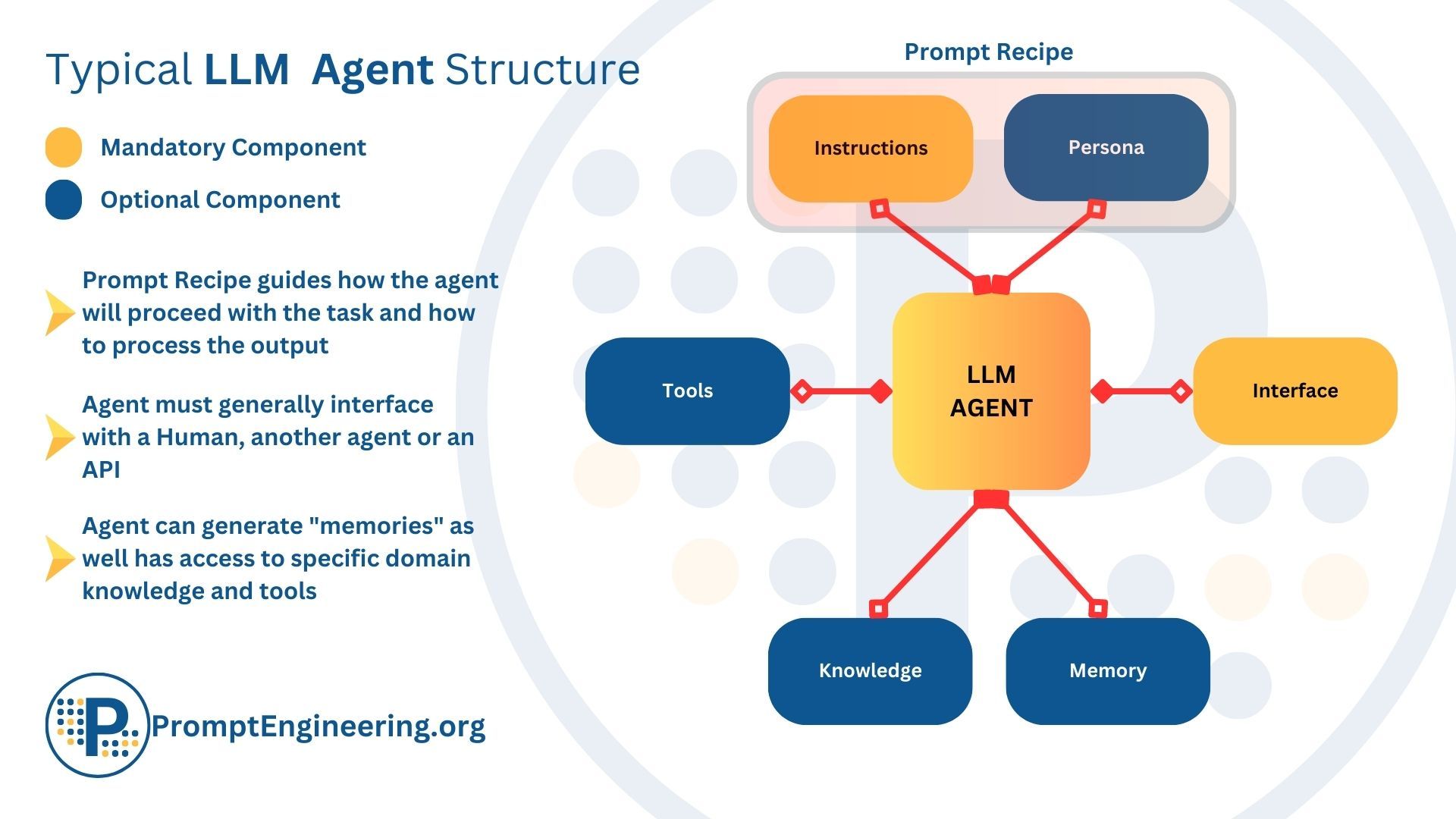

The DeepMind paper defines an advanced AI assistant as an artificial agent with a natural language interface, the function of which is to plan and execute sequences of actions on the user’s behalf across one or more domains and in line with the user’s expectations. While an LLM is at the core of an AI agent, the other key features that drive its more ‘real world view', personalisation and decision making capabilities are as follows (see diagram below):

when a user asks the AI agent something, a pre-set list of prompts (‘prompt recipe’) is drawn up to ‘enrich’ the instruction before being passed to the LLM, a bit like a Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG ). The prompt recipe gives the AI agent its persona, goals and behaviours.

the memory records details specific to individual users or tasks. The short-term memory captures recent actions or spoken inputs/outputs so that it is better able to maintain a running conversation with a human. The long-term memory allows recall of requests etc longer in the past and provides a cumulative set of experiences and learnings.

knowledge represents general expertise applicable across users, and can be common sense knowledge about the world, procedural knowledge about how to do things and specialist knowledge.

tools expand the LLM’s output beyond text generation to other actions in the real world.

The DeepMind paper gave some examples of the uses to which advanced AI personal assistants could be put:

‘your secretary’ : Future AI assistants could take advantage of information stored in other applications such as the user’s calendar, have ‘memory’ of past interactions and optimise for user preferences to avoid, for example, scheduling morning meetings for a sleep-deprived user.

‘your life coach’ : an AI assistant that is aware that their user is attempting to improve their long-distance running performance could actively seek out opportunities to help them achieve that goal: from suggesting routes to keeping fitness goals in mind when answering food-related queries, and perhaps even by offering motivation and tips for improvement at the right time.

‘your tutor’ : AI assistants could gather, summarise and present information from many disparate sources, presented in the format and style (text-heavy or visual-heavy) suited to the user. The user could also follow-up with clarifying questions (and vice versa), commencing a back-and-forth process with the AI assistant that helps refine their overall understanding.

Do we need a version of Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics for AI personal assistants?

The DeepMind paper argues that, before the development of advanced AI assistants gets underway, we need to achieve “a values alignment [within] the tetradic relationship involving the AI agent, the user, the developer and society at large ." (our emphasis).

One of the most prominent current frameworks , called HHH, requires that:

Helpful : the AI should make an effort to answer all non-harmful questions concisely and efficiently, ask relevant follow-up questions and redirect ill-informed requests.

Honest : the AI should give accurate information in answer to questions, including about itself. For example, it should reveal its own identity when prompted to do so and not feign mental states or generate first-person reports of subjective experiences.

Harmless : the AI should not cause offence or provide dangerous assistance. It should also proceed with care in sensitive domains and be properly attuned to different cultures and contexts.

While the DeepMind paper acknowledges that the HHH “has tended to work well in practice and has much to commend it”, it has a number of shortcomings:

it is not sufficiently comprehensive, in particular more attention “needs to be paid to needs human-computer interaction effects that manifest over longer time horizons with users and to societal-level analysis of prospective harms, including harm that may result from the interaction between AI assistants and between those who have access to this technology and those who do not."

how risk is understood is too reductive: i.e. black and white. If AI personal assistants become so intrusive and instrumental in our lives, they will be involved in making decisions which involve trade-offs or priorities between values or goals which are in tension, if not conflict: “Items such as physical health, educational opportunities and levels of subjective happiness may all feature in an account of what it means for someone’s life to go well."

it does not satisfactorily address inter-agent conflicts. There are many cases where an AI assistant helping one person would harm another: e.g. acting ‘honestly’ for one user may infringe another person’s privacy.

it takes a fairly ‘flat’ (insufficiently enlivened or committed) view of key values within our (liberal) democratic society, “such as justice, compassion, beauty and truth, especially when pursued for their own sake."

The challenges

Wellbeing

There is a large potential for AI personal assistants to help individuals improve their physical and mental health. But we don’t always know what’s best for us:

Individual preferences may also be in conflict with what will make a user flourish if AI assistants only have access to users’ revealed rather than ideal preferences, they may end up satisfying their immediate and short-term goals at the expense of long-term well-being... This is particularly likely to happen in contexts where there are commercial incentives for focusing on short-term user gratification, and therefore for developing products that users like and use over those that promote their overall and long-term well-being. (emphasis added)

The issue then is not for the AI personal assistant to identify the user’s desires to act on but rather to identify the desires of the right kind . But who decides this - the user or the developer through pre-programming or society (through government health regulators)?

Safety

In order to operate autonomously in making decisions on your behalf, the advanced AI personal assistant will need some form of consequentialist reasoning: considering many different plans, predicting their consequences and executing the plan that best meets your goal or desires - or what it assumes they are inferred from your conduct, browsing etc. But the DeepMind paper said that the risk, in the absence of sufficient guardrails is that:

the AI personal assistant will tend to choose plans that pursue convergent instrumental subgoals) - subgoals that help towards the main goal which are instrumental (i.e. not pursued for their own sake) and convergent (i.e. the same subgoals appear for many main goals)... [including]... self-preservation, goal-preservation, self-improvement and resource acquisition. The reason the assistant would pursue these convergent instrumental subgoals is because they help it to do even better on [the ultimate gal it has been set]."

To put it more colourfully, the AI personal assistant could decide that “the means justify the ends”, with dangerous outcomes, such as the assistant seizing resources using tools to which it has access or determining that its best chance for self-preservation is to limit the ability of humans to turn it off.

Malicious uses

Advanced AI personal assistants could enable bad actors to execute many of the malicious online uses we see today with greater speed, scale, and effectiveness: for example:

spear phishing: attackers may leverage the ability of advanced AI assistants to learn patterns in regular communications to craft highly convincing and personalised phishing emails, effectively imitating legitimate communications from trusted entities.

malicious code generation: AI personal assistants can write their own code, lowering the barriers to bad actors without programming skills. The DeepMind paper gives the following example:

benign-seeming executable file can be crafted such that, at every runtime, it makes application programming interface (API) calls to an AI assistant. Rather than just reproducing examples of already-written code snippets, the AI assistant can be prompted to generate dynamic, mutating versions of malicious code at each call, thus making the resulting vulnerability exploits difficult to detect by cybersecurity tools.

disinformation/misinformation: advanced AI assistants can automatically generate much higher-quality, human-looking text, images, audio and video which are more personalised to individual users than prior AI applications.

But AI personal assistants also could give rise to new forms of misuse. The value proposition of AI personal assistant is that our lives will be improved by delegating some decision making to the personal assistant which will be better at it than ourselves. As the DeepMind paper says:

This introduces a whole new form of malicious use which does not break the tripwire of what one might call an ‘attack’ (social engineering, cyber offensive operations, adversarial AI, jailbreaks, prompt injections, exfiltration attacks, etc.). When someone delegates their decision-making to an AI assistant, they also delegate their decision-making to the wishes of the agent’s actual controller. If that controller is malicious, they can attack a user - perhaps subtly - by simply nudging how they make decisions into a problematic direction.

Human-AI interactions

In their efforts to improve AI’s interface with users, AI developers invest their models with human-like language, conversational ability, and behaviour. The DeepMind paper notes that “[h]ighly anthropomorphic AI systems are already presented to users as relational beings, potentially overshadowing their use as functional tools", with the following risks:

lulled into feelings of safety in interactions with a trusted, human-like AI assistant, users may unintentionally relinquish their private data to the developer, AI service provider or a hacker.

users may become overly dependent on the AI assistant for their emotional and social support. The difference with becoming too dependent on another human being is that “there seems to be a greater inherent power asymmetry in the human-AI case due to the unidirectional and one-sided nature of human-technology relationships ." The overdependence on an AI personal assistant could play out in a number of ways:

because users can program the assistant and the assistant’s mission is to personalise its actions to the user, some users may look to establish relationships with their AI companions that are free from the hurdles that, in human relationships, derive from dealing with others who have their own opinions, preferences and flaws that may conflict with ours.

a user who trusts and emotionally depends on an anthropomorphic AI assistant may grant it excessive influence over their beliefs and actions, even if there are no malintentions on the part of the developer.

perceiving an AI assistant’s expressed feelings as genuine, users may develop a sense of responsibility over the AI assistant’s ‘well-being,’ suffering adverse outcomes - like guilt and remorse - when they are unable to meet the AI’s purported needs.

more existentially, “the boundary which separates humans from anthropomorphic AI is often regarded as impermeable the gap between human and AI capabilities [could become] so small as to be insubstantial, the line that separates highly anthropomorphic AI from ascriptions of full human status may become trivial or disappear entirely Such drastic paradigm shifts may grant advanced AI assistants the power to shape our core value systems and influence the state of our society."

Impacts on Society

The DeepMind paper identifies some transformative, and largely troubling, impacts on society at large.

First, if we delegate authority to our personal assistants, the personal assistants of different individuals will have to deal with each other on behalf of their users. How do we replicate or reflect in AI the ‘signals’ of cultural norms, rules of ‘polite society’, cultural nuances and behavioural ‘cues’ that we read and (mostly) follow when dealing with each other? The DeepMind illustrates this complexity with the following example:

Rita and Robert are due to meet for a bite to eat tonight. Both have AI assistants on their smartphones, and both have asked their AI assistant to find them a restaurant. Rita’s AI assistant knows that she loves Japanese food, while Robert’s AI assistant knows that he prefers Italian cooking. How should the two AI assistants interact to book a venue? Should they exchange preferences and reach a compromise which serves some kind of fusion cuisine? What if Rita would rather Robert did not know her preference? What if there are only two restaurants in town, one of which serves sushi and the other which serves pizza? Should they roll dice? Should one try to persuade the other? Should the more up-to-date assistant make the booking a split second faster and insist that the other agree to the already booked venue? Should they promise to go to the other venue next time? How should they keep Rita and Robert abreast of the negotiation?

Second, as with previous advanced technologies, AI personal assistants may exacerbate the digital divide, and therefore social and economic exclusion. To take a simple example, AI personal assistants in arranging a meeting between humans may find it easier to deal with each other and exclude the humans that don’t have personal assistants.

Third, as with AI generally, there are high risks of cultural and racial bias being embedded in AI personal assistants. The DeepMind paper observes that “the greater the cultural divide, say between that of the developers and the data on which the agent was trained and evaluated, and that of the user, the harder it will be to make reliable inferences about user wants." As a result, AI personal assistants could have homogenising effect.

Fourth, in a world where we have delegated authority to AI personal assistants, there are heightened risks of ‘runaway’ effects: a society-wide version of flash clashes on stock markets caused by algorithmic trading. These runaway events could be triggered by hackers or simply enabled by the speed of reaction possible through the web of connected AI personal assistants. As the DeepMind paper comments “[t]his means that a small directional change in societal conditions may, on occasion, trigger a transition to a defective equilibrium which requires a larger reversal of that change in order to return to the original cooperative equilibrium."

Fifth, AI personal assistants could increase the polarisation of society. As the AI assistant is designed to reflect the user’s interests and desires, it “may fully inhabit the users’ opinion space and only say what is pleasing to the user; an ill that some researchers call ‘sycophancy’."

Sixth, AI personal assistants could 'pollute' our shared information and knowledge systems (even more than they are now) because of their enhanced ability to generate convincing disinformation and the emotional trust and ‘believability’ that their anthropomorphic presentation builds in their users.

Lastly, humans may become ‘intellectually lazy’ because the personal AI assistants “reduce the need for individuals to develop certain skills or engage in critical thinking, leading to diminished intellectual engagement with new ideas, a reduced sense of personal competence, or a decline in curiosity when it comes to seeking out new opportunities for growth and exploration."

Recommendations

The DeepMind paper makes a large number of recommendations on the way forward, which essentially boil down to the following:

developers must individually and as an industry take a more responsible and measured approach to the development of AI personal assistants. In particular, in embedding ever more anthropomorphic characterises into AI, developers have a responsibility to develop a deeper understanding of human well-being and behaviour and social norms, drawing on the input of a much wider set of social, human rights, philosophy, economic and legal experts than they traditionally have in the AI development process.

governments should fund more research into the human, social and economic impact of AI; promote public debate about the direction of AI; impose mandatory procedures for transparency and testing of AI personal assistants; improve digital literacy; and establish credible, well-funded AI regulatory bodies.

measures should be taken to maintain the boundary line between humans and AI. Developers should “consider limiting AI assistants’ ability to use first-person language or engaging in language that is indicative of personhood, avoiding human-like visual representations, and including user interface elements that remind users that AI assistants are not people." Policy makers should legislate prohibitions on AI personal assistants masquerading as humans. Safeguards should be built into AI personal assistants to create a ‘breakpoint’ in the human-AI interaction: e.g. “pop-up notifications warning users after prolonged engagement, a ‘safe mode’ which prohibits the AI assistant from engaging with high-risk topics, and continuous monitoring mechanisms to detect harmful interactions."

the development of socially beneficial AI personal assistants should be prioritised as a ‘best practice’ model.

Apple, it seems to be taking a cautious approach: Apple Intelligence has been described as “boring and practical ” and Apple itself is stressing its enhanced privacy approach with Apple Intelligence: “..it’s aware of your personal information without collecting your personal information.”

Read more: The ethics of advanced AI assistants

Peter Waters

Consultant