The UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) launched its review of AI foundation models (FMs) competition in May 2023 and published an initial report in September 2023 (see our review in ‘ Will Big Tech dominate AI? Part 1 ’ and ‘ Will Big Tech dominate AI? Part 2 ’).

Following extensive engagement and ongoing monitoring of market developments, the CMA recently published an update paper and technical update report . Whereas the initial report stayed largely neutral as to potential market outcomes, the CMA’s thinking now appears to have crystallised into concerns that the FM sector is developing in ways that risk negative market outcomes.

Why the shift in view?

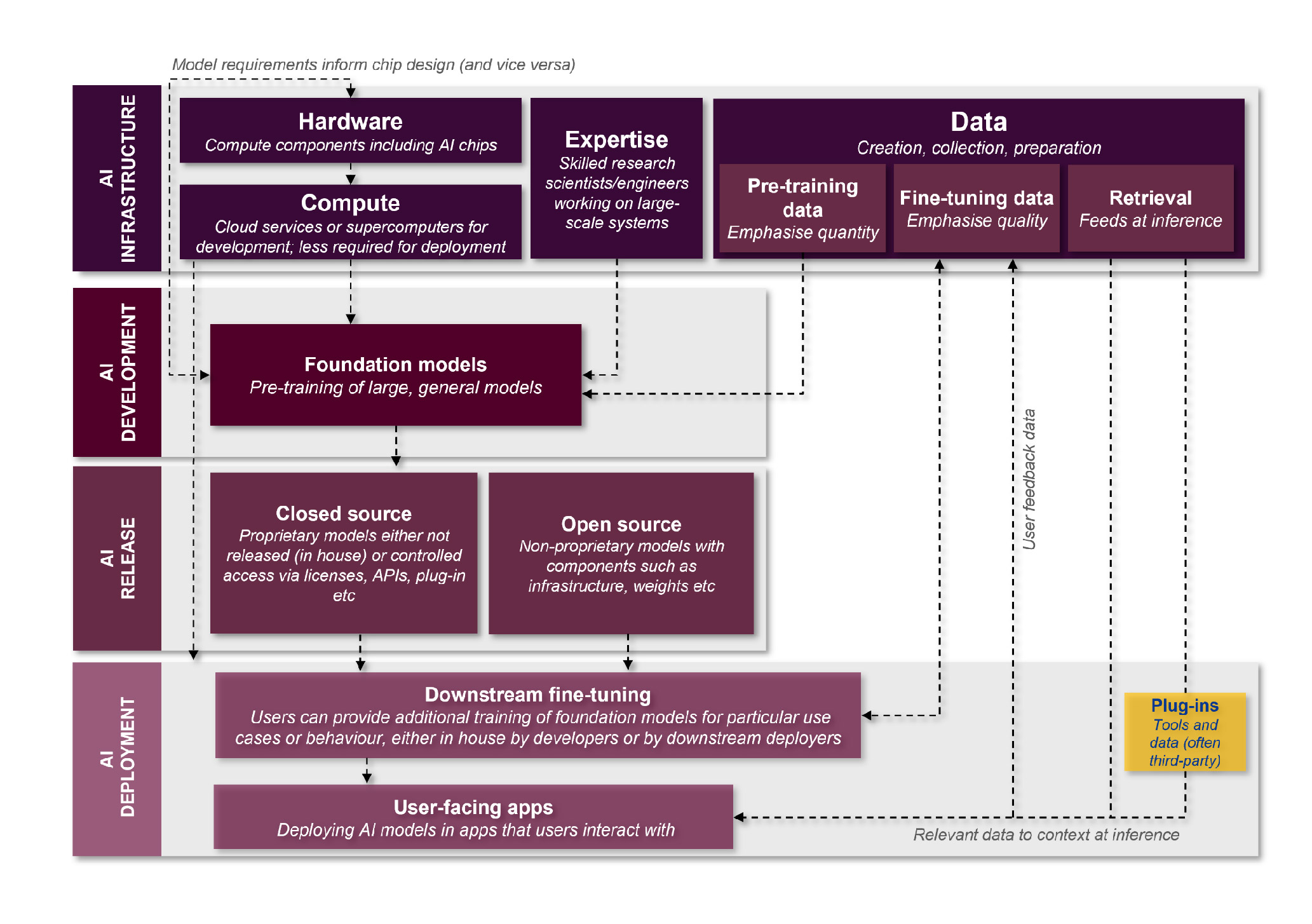

The CMA’s understanding of the FM value chain

The CMA has updated Figure 3 from its initial report, reflecting its further consideration of the FM value chain, as shown in Figure 1 of its technical update report:

Key changes since the initial report include:

adding hardware to AI infrastructure, which (although unexplained) potentially reflects the increasingly prominent role played by AI accelerator chips, as shown by the meteoric rise of Nvidia; and

separating AI release from AI deployment, in part due to the emergence of platforms for accessing FMs.The CMA’s AI Principles.

The CMA’s AI Principles

Further, the CMA has updated its set of principles for an ‘idealised’ AI supply chain delivering positive outcomes for consumers, businesses, and the economy in Figure 3 of its update paper as follows:

Key changes since the initial report include:

flexibility being collapsed into choice, given that both principles sought to address the same underlying objective of choice in how to develop, release and deploy FMs; and

greater emphasis on partnerships and integrated firms, which as we discuss below seems to be the main driver of the CMA’s shift in thinking about the negative direction of market development.

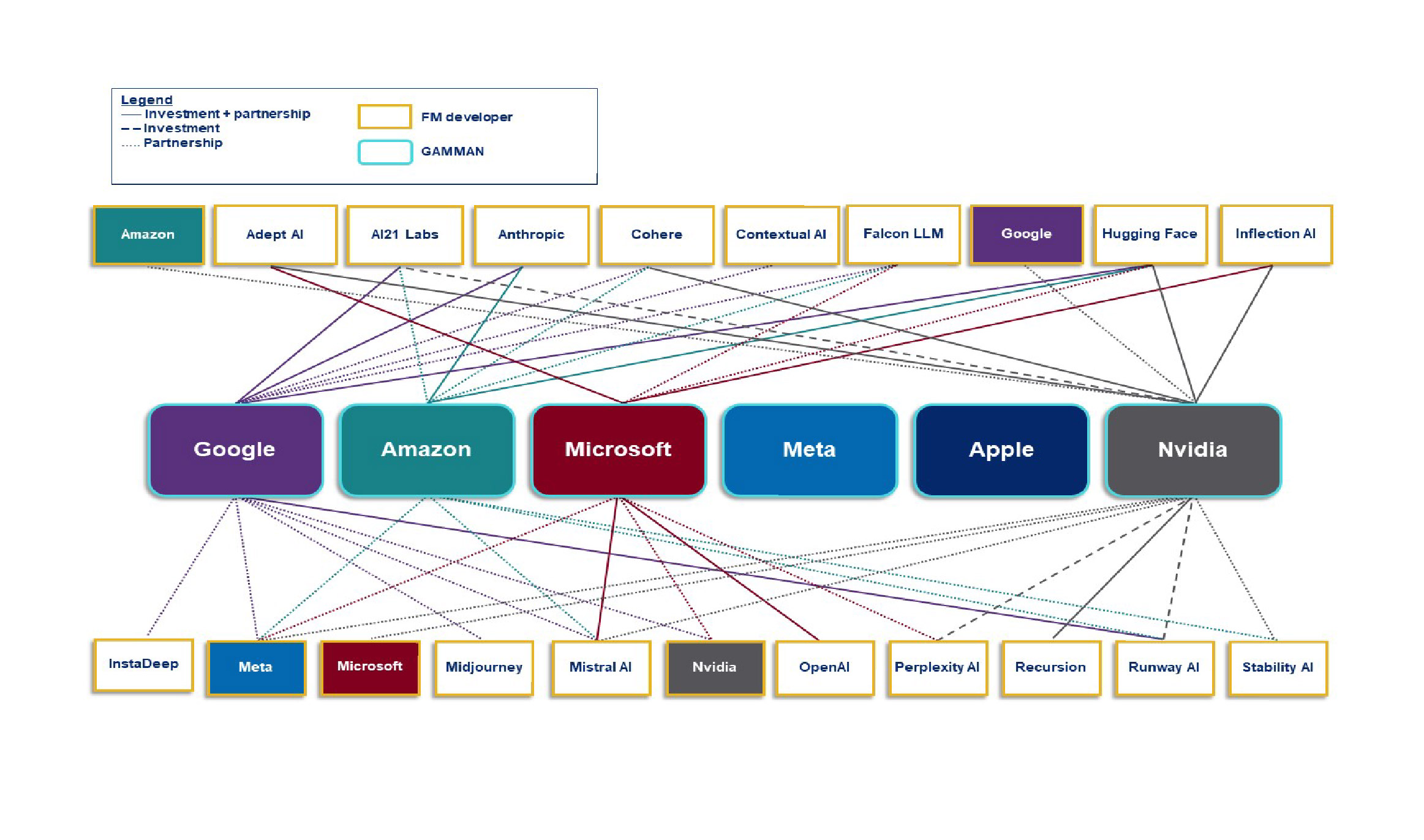

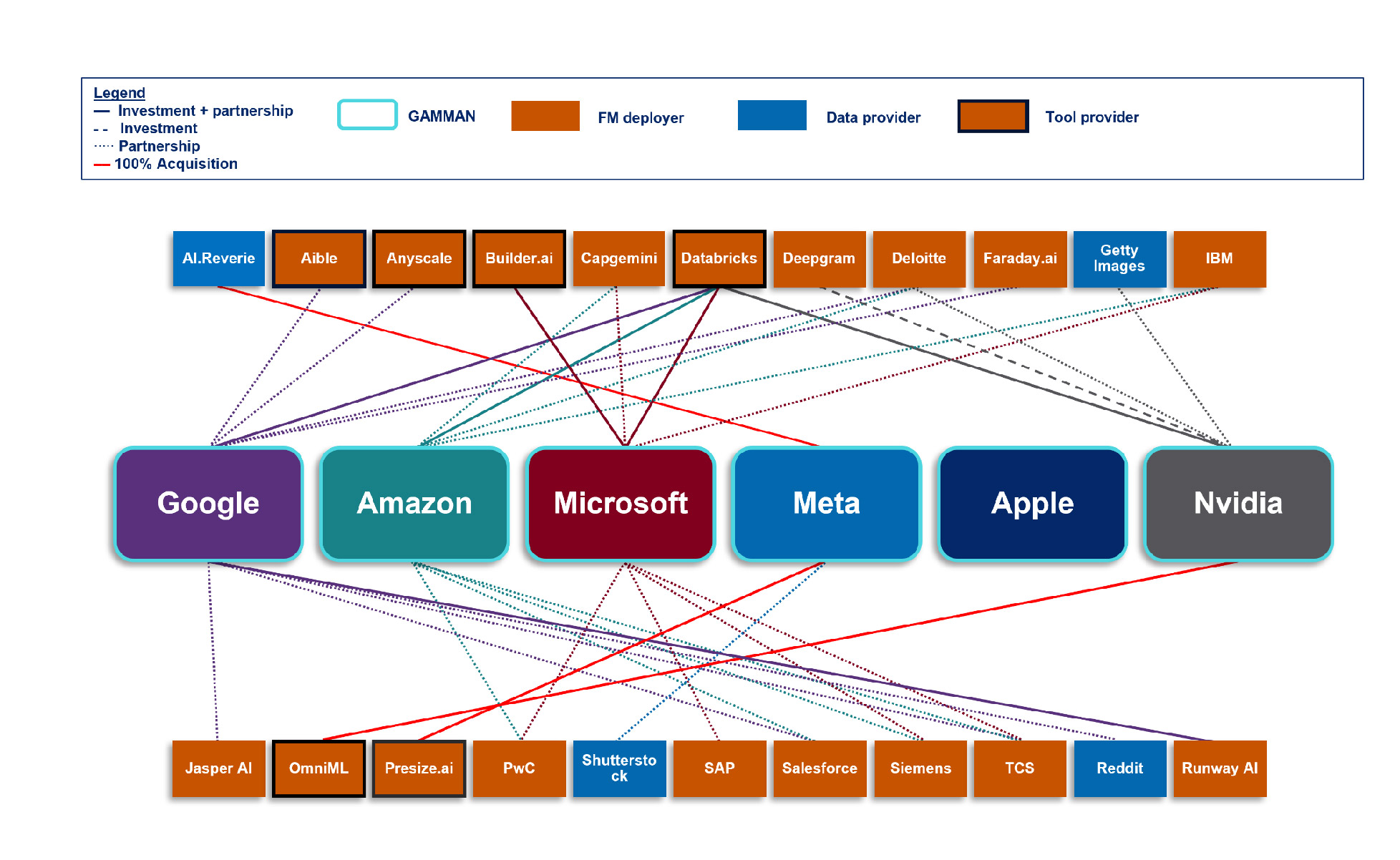

The CMA’s concerns

In a nutshell, the CMA’s concerns are ‘all about vertical integration’, which it considers is achieved through a range of partnerships and investments, as illustrated by the CMA through the following diagrams (GAMMAN = Google, Amazon, Microsoft, Meta, Apple and Nvidia):

GAMMAN relationships with FM developers (Figure 5 of the update paper):

GAMMAN relationships with FM deployers (downstream from FM developers, which build and adapt more specialist models using generative AI) (Figure 8 of the technical update report):

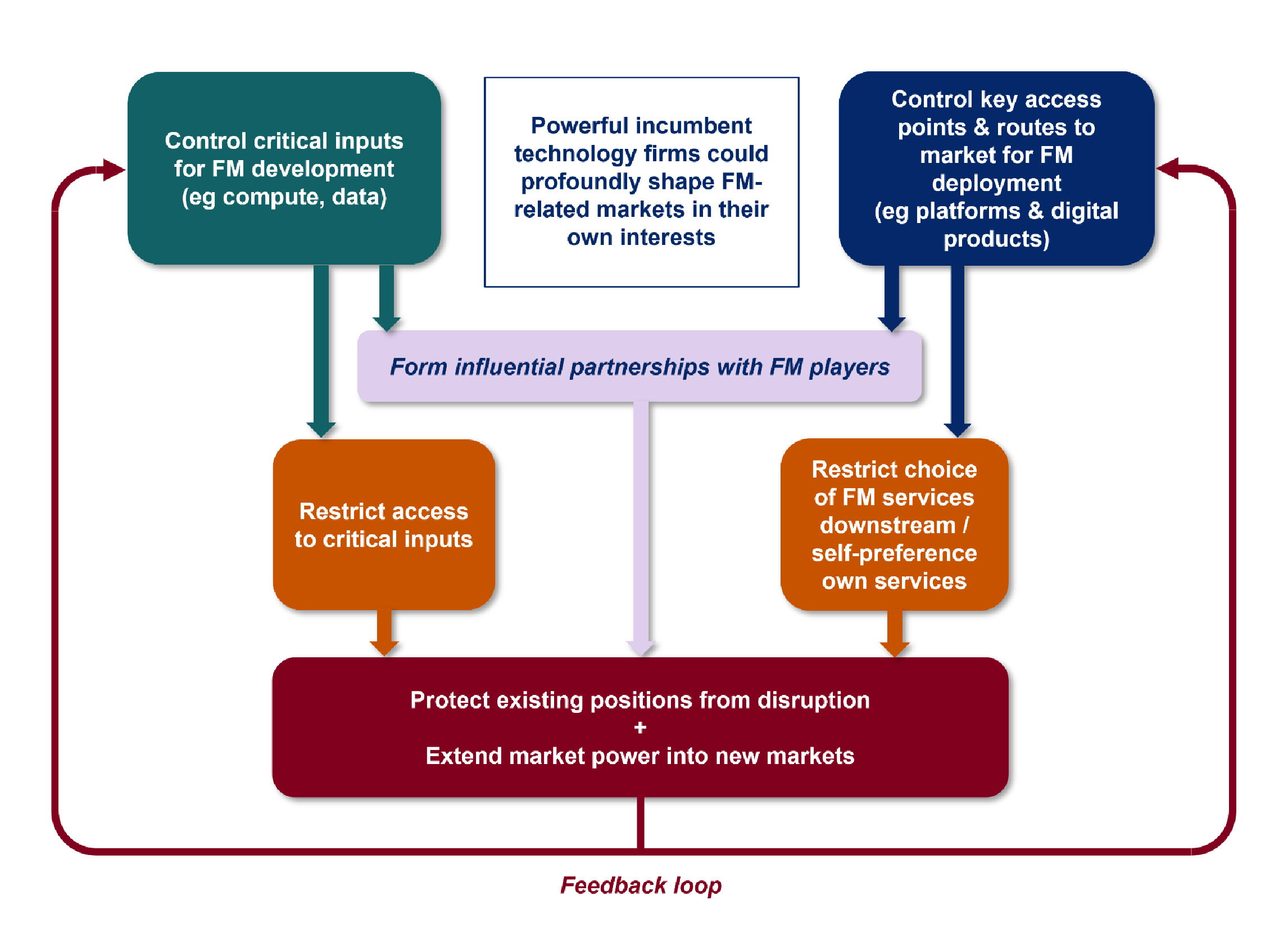

In the context of these market relationships, the CMA has identified three key interlinked risks to fair, open, and effective competition:

Firms that control critical inputs for developing FMs may restrict access to them to shield themselves from competition.

Powerful incumbents could exploit their positions in consumer or business facing markets to distort choice in FM services and restrict competition in FM deployment.

Partnerships involving key players could reinforce or extend existing positions of market power through the value chain.

The CMA expressed concern that there could be a self-perpetuating and accelerating feedback loop, depicted as follows in Figure 6 of its update paper:

But is it more complicated than this?

These concerns are strongly reminiscent of those expressed by regulators in relation to digital platforms more generally, being theories of harm based on vertical integration and leveraging of market power in related markets.

While this risk cannot be dismissed, there is no certainty that FM markets will behave in the same way as the CMA considers earlier technology markets behaved, given the underlying differences in the technology. Some of the CMA’s own findings seem to point in a different direction.

Diversity of FMs

In its initial report, the CMA observed that the FM sector seems to be highly dynamic and rapidly evolving, such that first mover advantage does not give rise to an unassailable lead and maintaining a competitive advantage requires continuous innovation. While the range of technology partnerships and investments may have spread and deepened since the CMA made these initial observations, other factors exhibiting the dynamism and diversity of AI markets also seemed to pick up speed and force.

From September 2023 to March 2024, 120 FMs were publicly released, bringing the total number of known FMs globally to over 330 - an increase of approximately 57% over six months.

Although Open AI’s GPT-4 remains a leading FM, competitors have recently released FMs with comparable, if not superior, capabilities, as measured by performance across a number of benchmarks.

Newer FMs also exhibit:

multimodal capabilities, providing for text, image, audio and video inputs and outputs;

the ability to process increasing amounts of data, with longer context windows; and

incorporation of both static and dynamic knowledge bases through retrieval-augmented generation (RAG ), facilitating introduction of specific and up-to-date information.

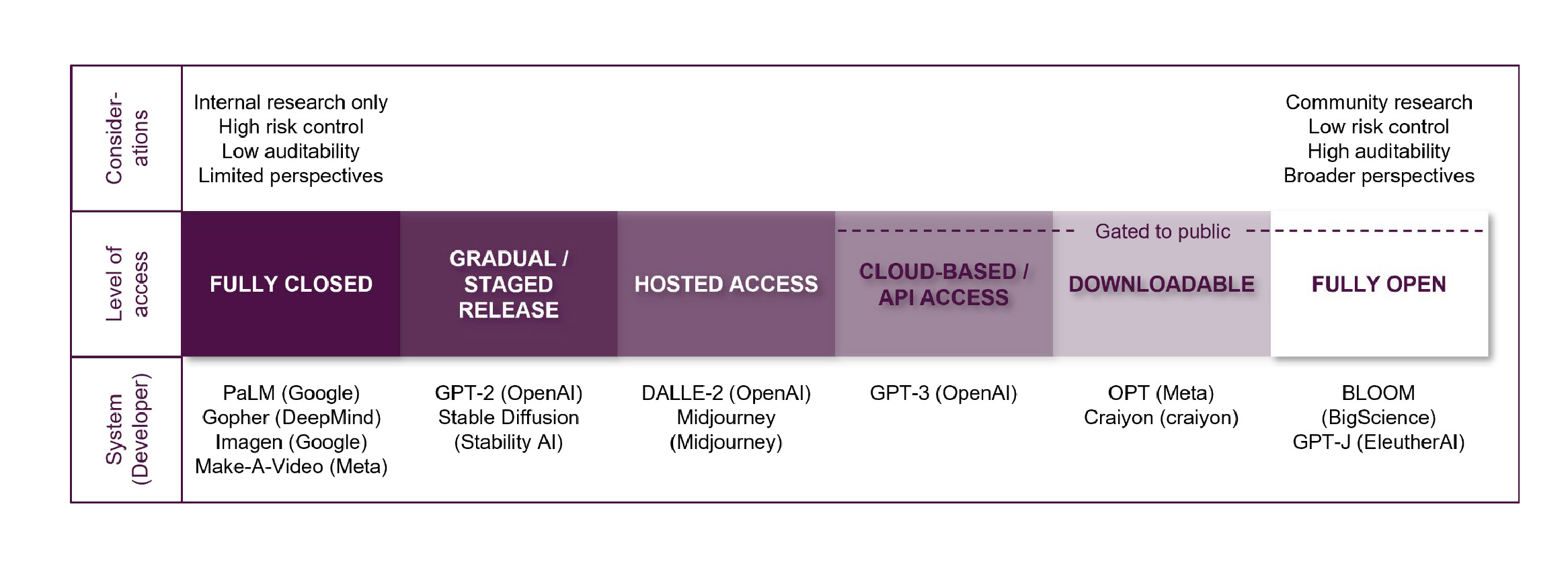

Probably the most striking difference from previous technology markets is the apparent power of open-source models. While some FMs are closed (e.g. proprietary, commercial or internal-use models), others are open-source (typically being freely available, including for modification and redistribution, with visibility of the underlying source code). These two extremes can be seen as opposite ends of a spectrum, as shown by the following diagram at Figure 17 of the CMA’s technical update report:

The CMA acknowledged that open-source FMs remain an important force for competition and innovation, supporting access to FMs for users without existing access to key inputs required to build a FM from scratch, allowing a broader range of developers to use, build and deploy AI systems at a reduced cost. Of the FMs released between September 2023 and March 2024, at least 52 are open-source and 21 are closed or limited.

Technology firms are also far from monolithic in their market and product strategies. Stable Diffusion, one of the most popular text-to-image generators, is open-source. Meta is also pursuing an open-source approach through Llama, a large language model that is a powerful alternative to OpenAI’s closed GPT models, like those that power ChatGPT. Meta’s Chief AI Scientist has said that, from a technology viewpoint , “[o]pen source AI models will soon become unbeatable. Period.” and, from a moral or social viewpoint , open source should prevail because:

"In the future, our entire information diet is going to be mediated by [AI] systemsThey will constitute basically the repository of all human knowledge. And you cannot have this kind of dependency on a proprietary, closed systemPeople will only do this if they can contribute to a widely available open platform. They're not going to do this for a proprietary system. So the future has to be open source, if nothing else, for reasons of cultural diversity, democracy, diversity. We need a diverse AI assistant for the same reason we need a diverse press."

There is also an assumption that ‘big is better’, such that only large technology firms have the resources to build FMs. However, the varied use cases for FMs also mean that size isn’t everything. Often, the full capability and set of parameters of large, general purpose FMs is not required for more specialised uses - indeed, quality can be more important than quantity, as small FMs trained using curated data (including distillation or fine-tuning) can outperform larger counterparts in undertaking specific tasks. An IBM executive has commented that small language models ‘punch above their weight’:

"They are generally more lightweight and require less computational power, making them easier to deploy and potentially more cost-effective. Additionally, their smaller size often makes them more transparent and explainable, easier to manage in context of risk, compliance and overall AI governanceWhile capable, smaller models might not match the sheer breadth and depth of very large LLMs. But used in specific expert niche (for example finance, legal, manufacturing), they can deliver very good results."

Further, the trend of ‘Honey, I shrunk the FM’ has reached the point where advances in both software and hardware have facilitated local FM deployment on consumer devices. Key benefits of on-device FMs from a user perspective include lower latency, increased privacy and security, and not needing an internet connection. From a developer and deployer perspective, on-device storage and inference of FMs reduces the need for compute.

In terms of access to FMs, marketplace platforms currently support different types of model access, giving customers a broad range of FMs from which to choose, including on both a free and paid (including subscription) basis.

Key inputs

As outlined in the CMA’s diagram of the FM value chain, critical inputs for FM development include:

hardware;

compute;

expertise; and

data.

The CMA observes that incumbent technology companies typically have greater access to these resources.

That said, barriers to entry, in the form of the need for or access to those resources, have been significantly eroded, such that they do not represent an insurmountable obstacle.

On the hardware front, supply of AI accelerator chips required to provide compute has been constrained by limited manufacturing capacity, resulting in long wait times (particularly for state-of-the-art chips). While Nvidia is the clear market leader in this space, competitors are also ramping up production, with some FM developers starting to build their own chips. Further, broadly consistent with Moore’s Law, the computing power of chips has continued to increase rapidly while the per-unit cost of computing power has decreased greatly.

Although larger FMs requiring more compute are being developed, all else being equal, compute requirements for FMs have been decreasing, including through use of smaller, specialised FMs and on-device deployment of FMs (as discussed above), as well as new and more efficient model architectures. Further, FM developers do not need to have their own compute, with the primary means of access being via cloud service providers, in addition to partnerships.

In relation to expertise, there is strong demand for researchers with relevant expertise from FM developers. A significant parallel development is that regulators in many jurisdictions around the world have been cracking down on non-compete clauses, including the US Federal Trade Commission announcing a rule banning non-competes in April - this may limit the ability of incumbents to lock up talent through use of such clauses. Substantial investment in training to upskill personnel has also been occurring, which will ease the skill shortage going forward.

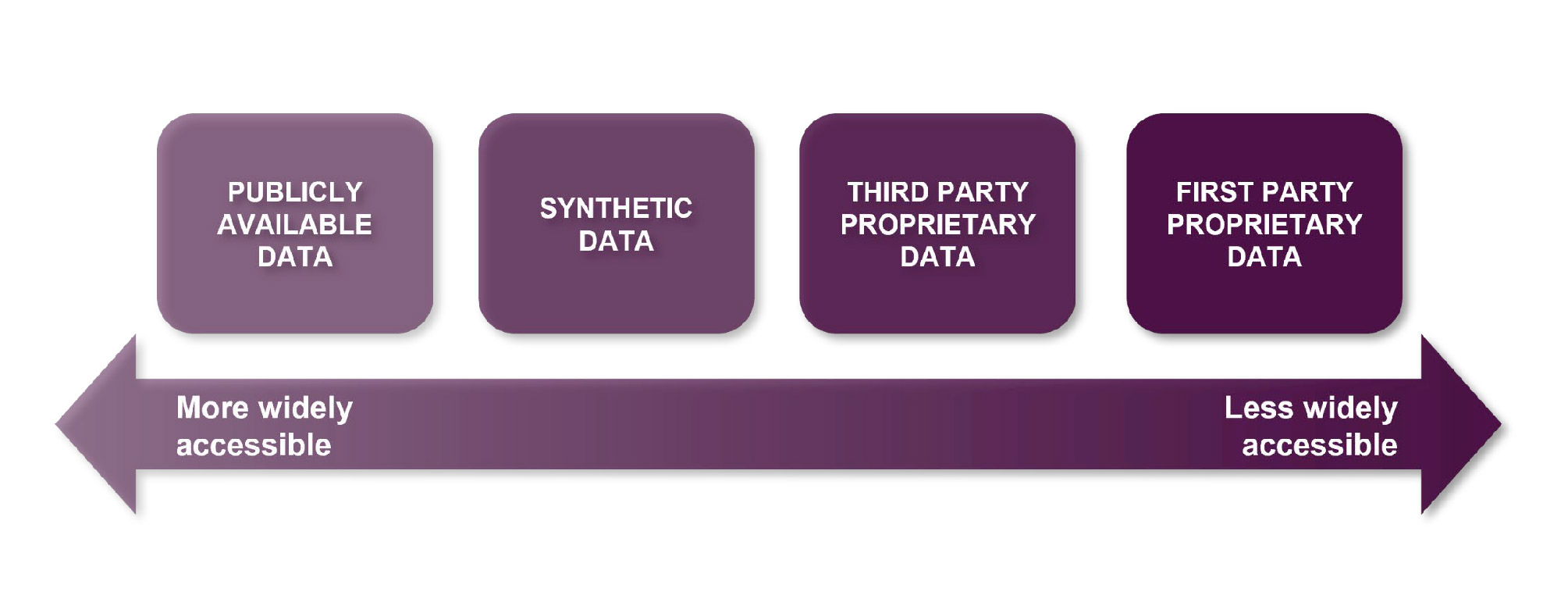

The following diagram at Figure 13 of the CMA’s technical update report depicts different types of data sets and their associated accessibility:

In a similar vein to compute, FM developers do not necessarily need to have their own stockpiles of data, including due to the availability of pre-trained open-source FMs and publicly available data. The CMA’s initial report explored whether there was scope for synthetic (that is, artificially generated) data to be used to train FMs, although it had not yet been tested at scale. Since the initial report was published, synthetic data has been used to pre-train and fine-tune several FMs, suggesting increasing viability, although some uncertainty remains around its suitability and accessibility. Third party proprietary data (including, in some instances, web-scraped data) has become the subject of intellectual property enforcement action, such that FM developers are increasingly seeking to ensure lawful access through mechanisms such as partnerships and licensing agreements.

More broadly, the CMA has noted the need to raise large amounts of funding to support FM development. Given the extent to which generative AI has captured the public imagination, there has been substantial capital investment in the sector despite the high interest rate environment. Further, Stanford University Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence’s recent global survey shows that venture capital is increasingly being spent on firms developing new (as opposed to existing) FMs.

Conclusion

The CMA’s concerns about the trend to competitively constrained AI markets are certainly not baseless and are shared by EU, US and Australian antitrust authorities.

But that said, it was easier to argue that earlier, vertically integrated generations of technology, such as PSTN telecommunications networks or pre-programmed software, beget vertically integrated operators (or maybe vice versa). Yet with AI, we have open vs closed models vying with each other; small LLMs challenging large LLMs in many functional areas; AI models (even closed models) can be fine-tuned and adapted by intermediaries; and users themselves can adapt AI models (through RAG and prompt engineering). It may be hasty to treat AI competition as another ground hog day for anti-competitive vertical integration.

Read more: AI Foundation Models: Update paper

Peter Waters

Consultant