The COVID-19 pandemic, as the first global public health crisis of the algorithmic age, saw governments turn to new data-driven technologies and AI tools at an unprecedented rate to support the pandemic response.

However, a recent report by the Ada Lovelace Institute across 34 countries has found little evidence to show that these digital tools actually worked in reducing the spread of COVID-19 or had a positive impact on people’s health behaviours.

COVID-19 apps

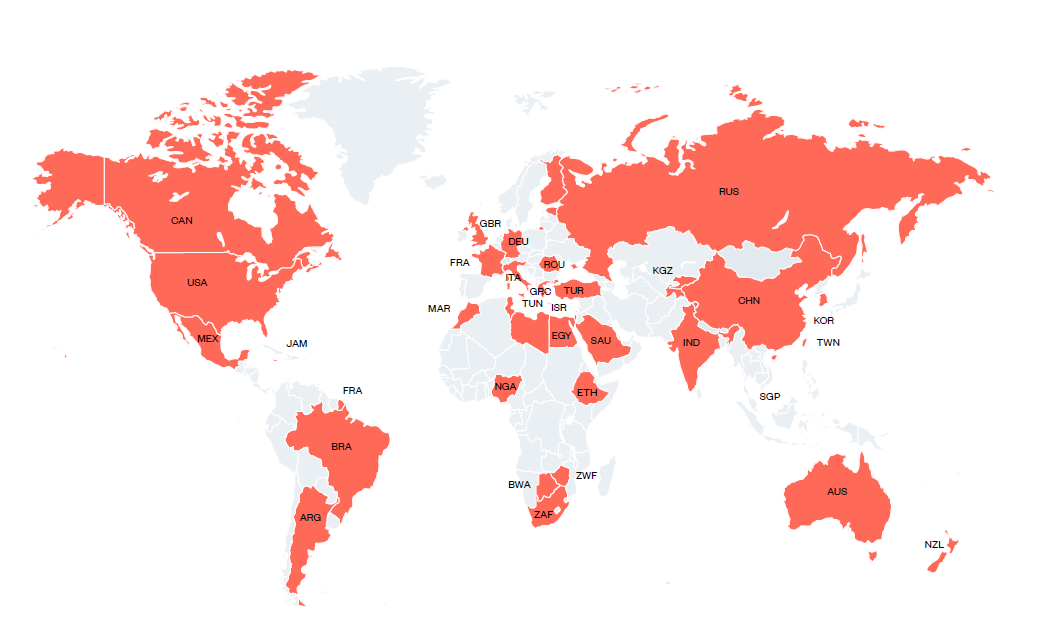

The countries included in the Lovelace study are depicted below:

The two primary COVID apps attempted to be deployed on a mass basis in these countries were contact tracing apps and digital passports. Both sought to determine an individual’s risk to others and to allow or restrict freedoms accordingly.

The contract tracing apps:

there were two types of contract tracing apps: a centralised approach to contact tracing apps whereby users’ data was stored on a central server operated by public authorities; and a decentralised approach, with user data stored on users’ mobile phones and public authorities accessing the data on a back-end server (users were identified by arbitrary identifiers so that their locations and social interactions could not be reconstructed).

25 of the 34 countries in the Lovelace study introduced digital contract tracing apps.

The digital vaccine passports:

are digital health certificates used to prove individuals’ vaccine status or antigen test results to show recovery from the virus.

during the pandemic they were used domestically within a country to enable access to certain activities, such as workplaces, or for international travel.

all 34 countries in the Lovelace study introduced digital vaccine passports between January and December 2021. China and New Zealand were amongst the most strict in use of digital vaccine passports to restrict entry to domestic venues and international travel.

How big was the ‘techno-flop’?

While the Lovelace report finds significant evidentiary gaps regarding COVID-19 apps’ effectiveness as public health tools, the data that exists suggests a colossal, almost comical failure. For example:

Australia’s app over a 2-year period only notified a total of 17 individuals not found manually. France’s app sent only 14 notifications despite having over 2 million downloads by June 2020;

voluntary contact tracing app use in 13 countries found an average adoption rate of just 9%. Initial uptake went backwards in many countries as consumer privacy concerns mounted. The French Government reported that tens of thousands of citizens per day were deleting its contract racing app (which used a centralised model).

even use of decentralised contract tracing apps which were more privacy-enhancing struggled. There is evidence that millions of people who downloaded the NHS COVID-19 app (used in England and Wales) never technically enabled it.

To the extent that digital vaccine passport schemes relied on the assumption that an individual is a lower risk to others if they have been vaccinated, they were misconceived because there is no clear scientific evidence that being vaccinated reduced an individual’s risk of transmitting the disease.

The Lovelace report also found mixed experience of the impact of digital vaccination passports on vaccination rates (the theory being that the ‘reward’ of easier access to venues and travel would encourage vaccination):

in the majority of the EU countries, the vaccine passport requirement for domestic travelling and accessing different social settings appears to have led to higher vaccination rates: France, for example, saw a 15% rise in vaccination rates after the introduction of a digital passport scheme;

but levels of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance were low in West Asia, North Africa, Russia, Africa and Eastern Europe despite the use of digital vaccine passports: for example, only one in 4 Russians were vaccinated despite a planned mandatory digital vaccine passport scheme.

The Lovelace report identified a number of reasons behind the poor performance of COVID-19 apps.

Technical issues with COVID-19 apps

Some countries’ COVID-19 apps experienced significant technical issues due to their incompatibility with Apple/Google’s decentralised Exposure Notification protocol (GAEN API). This was particularly a problem faced by the centralised contract tracing apps, such as in France and Australia.

The Lovelace study found that 15 of the 25 countries in its study which deployed contract tracing apps used a decentralised model - less out of privacy concerns than ensuring compatibility with the GAEN API. Even countries such as the UK and Germany which originally followed a centralised model for contract tracing apps eventually had to deploy the GAEN API to enable their Bluetooth notification systems to work effectively.

Low levels of public acceptance

The Lovelace report found that the key reason for failure of COVID apps was the low rates of adoption and public support in many countries. This was not just a case of passive indifference or inertia: over half of the countries included in the study saw protests against COVID apps.

There were two exceptions, at different ends of the scale:

in China, the Health Code app was automatically integrated into users’ WeChat and Alipay e-commerce apps, so that they could only deactivate the COVID-related functionality by deleting these applications. Given that digital payments are the main method of payment in China, the Health Code app was effectively mandatory and as a result, there were over 900 million users of the app (out of 1.4 billion); and

in Canada, where its app was voluntary, the government spent C$21 million on a campaign to encourage Canadians to download and use the app, which marked Canada out from the other countries in the Lovelace study where uptake was voluntary. The evidence found that this campaign resulted in millions of downloads.

Digging into the global low uptake of COVID apps, the Lovelace study found two reasons.

First, unsurprisingly, the public legitimacy of COVID-19 apps depended on the public’s belief in the security and effectiveness of the apps and trust in government to protect their freedoms and privacy.

The biggest driver of public mistrust was the misunderstanding that contract tracing apps allowed governments to trace users’ movements. But the truth, never effectively communicated by governments (other than in Canada), was that contract tracing apps, especially those using Bluetooth and the GAEN API, did not collect geolocation data but only that an incident of proximity at an unidentified place with an infected person has occurred.

The second reason is related, but more deeply seated - and was best illustrated by what happened in China when mandatory use of the contract tracing app was lifted. The Lovelace study posited that the widespread celebratory content on Chinese social media indicated “that people were happy to make decisions and take precautions for themselves rather than rely on the Health Code algorithm.” There is nothing more personal to each of us than our health and ultimately, while we may make better decisions when informed, we think we are placed to decide for ourselves rather than defer to an algorithm and the behavioural rules it triggered.

COVID-19 apps may have widened existing structural inequalities

Unsurprisingly, groups which already had low levels of trust in government were less likely to use COVID-19 apps. For example, in the UK:

42% of Black, Asian and minority ethnic respondents downloaded the NHS contact tracing app compared with 50% of white respondents;

13% of Black, Asian and minority ethnic respondents who did download the app then deleted the app compared with 7% of white respondents.

The COVID apps not only played into an existing well of distrust of government amongst minority and disadvantaged groups, but themselves entrenched or worsened inequities. As one commentary has observed :

"the rollout of COVID interventions in many countries has tended to replicate a mode of intervention based on ‘technological fixes’ and ‘silver-bullet solutions’, which tend to erase contextual factors and marginalize other rationales, values, and social functions that do not explicitly support technology-based innovation efforts ."

The Lovelace report also finds that digital vaccine passports for international travel increased global inequalities by discriminating against countries which could not secure adequate vaccine supplies.

COVID-19 apps were not governed well

The report concludes that most countries did not enact robust laws and regulations governing the use of COVID-19 apps or put in place effective oversight and accountability mechanisms. Only a few countries enacted new regulations to govern these apps, such as the UK, EU member states, Taiwan and South Korea.

Most countries used existing legislation which was not comprehensive, especially in countries with weaker data protection and privacy laws. This resulted in a lack of accountability for apps’ lack of effectiveness, technical problems and incidents of misuse and data leaks. For example, data from contact tracing apps was used in police investigations in Germany and Singapore and sold to third parties in the USA, while digital vaccine passport data was hacked in Brazil. These incidents reduced public trust in COVID-19 apps and the public’s willingness to use similar technologies in future public crises.

Sometimes humans are just better than algorithms

The biggest problem with ‘techno-solutionism’ is that it assumes that the replaced human processes, because they are slower or more resource intensive, are less effective than an algorithm. However, as the Lovelace report comments, human processes of contract tracing were a better tool:

“Manual contact tracing teams should ideally be trained to help individuals and families to access testing, identify symptoms, and secure food and medication when isolating. This type of in-depth case investigation and contact tracing requires knowing and effectively communicating with communities, which cannot be done via a mobile application.”

Conclusion

COVID-19 apps were essentially served as a barometer of public attitudes towards the use of new, data-driven health technologies in everyday contexts, and of the public’s willingness to share sensitive data and accept restrictions on their freedoms based on the apps’ guidelines.

The generally poor implementation of COVID-19 apps has probably meant that we have gone backwards in the use of digital tools to manage public health crisis - potentially even with a ‘spill over’ effect of eroding public trust in the use of data-driven technologies in everyday health contexts.

The Lovelace report makes the following recommendations to rebuild trust:

understand the varying impacts of apps’ different technical properties on people’s acceptance of, and experiences of, these technologies.

but also go further, by defining criteria for effectiveness using a human-centred approach that goes beyond technical efficacy and builds an understanding of people’s experiences, sliced by the socio-economic contexts.

effectively communicate the purpose of using technology in public crises, including the technical infrastructure and legislative framework for specific technologies, to address public hesitancy and build social consensus.

put in place redress mechanisms in cases of data leakage or misuse.

create monitoring mechanisms that specifically address the impact of technology on inequalities. Monitor the impact on public health behaviours, particularly in relation to social groups who are more likely to encounter health and other forms of social inequalities.

create specific guidelines and laws to ensure technology developers follow privacy-by-design and ethics-by-design principles, and that effective monitoring and evaluation frameworks and sunset mechanisms are in place for the deployment of technologies.

Read more: Lessons from the App Store

KNOWLEDGE ARTICLES YOU MAY BE INTERESTED IN:

AI Regulation in Australia: A centralised or decentralised approach?

Buy Now Pay Later - Preparing for tougher regulation

The impact of AI is getting very serious, very quickly

Peter Waters

Consultant