On 27 June 2024, the Grantham Research Institute (GRI) on Climate Change and the Environment published its annual ‘ Global Trends in Climate Change Litigation: 2024 Snapshot ’ Report (Report). This is the sixth report in the series of publications on climate litigation, produced by the GRI in partnership with the Sabin Centre for Climate Change Law (Sabin Centre). The Report considers developments in global climate change litigation in the calendar year 2023 and provides a quantitative analysis detailing the number of cases filed globally and a qualitative assessment examining trends and recurring themes.

KEY THEMES

Climate litigation is here to stay with 233 new climate cases filed in 2023, bringing the total number of cases recorded by the Sabin Centre to 2,666. Most of these have been filed since 2015, the year the Paris Agreement was adopted.

Australia and the United Kingdom have the second highest number of climate cases behind the United States, with a total of 132 and 139 cases respectively. The United States remains the country with the highest number of documented climate cases by a large margin: 1,745 cases in total and 129 of those filed in 2023.

Strategic climate litigation is increasingly being filed against private actors. Since 2015, more than 230 climate cases have been initiated against companies and trade associations. The largest number of cases (more than 60%) and the biggest success rate (more than 70% of finalised cases) is in relation to cases challenging 'climate-washing'.

The Report identifies 'transition risk' cases as a new category of strategic litigation: these cases challenge how low-carbon transition risk is managed by directors, officers and others in similar positions responsible for ensuring a business’s success. The Report notes that it expects to see considerable growth in this area.

Human-rights-based climate litigation is playing an important role, noting, in particular, the European Court of Human Rights decision in April 2024 in the case of KlimaSeniorinnen and Ors. v. Switzerland , which may signal a turning point in terms of the success rate of cases brought against government actors (which, up to this point, has been relatively low). Notably, human rights arguments are also being made in cases beyond specialist human rights courts and tribunals.

While the majority of cases identified pursue ‘climate-aligned’ outcomes, nearly 50 of the 233 cases initiated in 2023 were not aligned with climate goals. The Report identifies ‘non-climate-aligned cases’ as those where the court is used to advance agendas that seek to delay or dissuade climate action, such as ESG backlash cases and strategic litigation against public participation (SLAPP ) cases.

The Report anticipates that future trends will include cases challenging and testing responses to climate disasters, the application of criminal law and the concept of 'ecocide', and the convergence of environmental issues (e.g. plastic pollution), climate litigation and human rights.

What do the numbers say? The geographical scope of climate litigation continues to expand

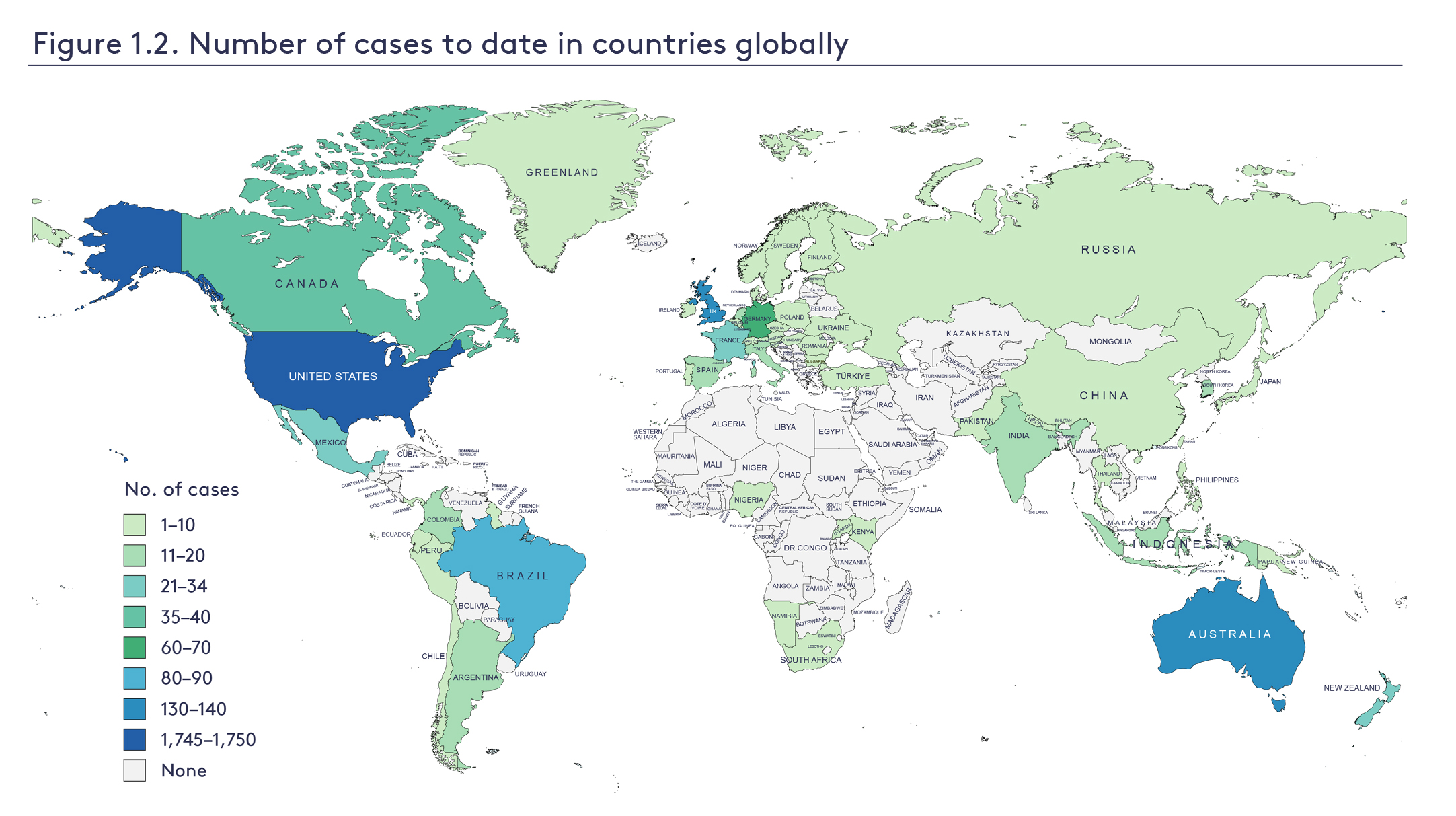

Climate change litigation captured in the Sabin Center’s climate change litigation database (database) has identified 2,666 ongoing or concluded cases of climate change litigation from around the world, of which 233 were filed in the calendar year 2023 (see Figure 1.2 below from page 11 of the Report).

The total number of cases filed appeared to have reached a peak in 2021 and the rate of increase may be slowing. The Report notes that this could be a result of delays in the data collection and/or that resources might be directed towards a smaller number of cases that are anticipated to have a more lasting or wide-ranging impact. There could also be a consolidation or stabilisation phase, where lawyers are waiting for decisions in existing cases before filing new ones. The political and regulatory climate in the relevant country will also be a contributing factor.

The growth in cases continues to vary across jurisdictions. Climate change litigation has been captured in the database in Panama and Portugal in 2023 (and older cases filed in Hungary and Namibia were identified for the first time). Climate litigation cases have now been identified in 55 countries.

In terms of the highest number of total cases, this remains the US (1,745 cases in total with 129 filed in 2023), followed by the UK (a total of 139 cases and 24 filed in 2023), then Australia (132 in total with 6 in 2023), Brazil (82 in total with 10 in 2023) and Germany (60 in total and 6 in 2023). Importantly, over 200 cases have now been identified in the Global South (with Brazil leading the way).

Diversity in 'strategic' climate litigation - more is more

We are continuing to see cases aimed at influencing the broader debate around decision-making related to climate change. These claims are being made on an increasingly diverse basis and a broader range of entities are being targeted.

Broadly, the Report has identified the following categories of strategic litigation (see Table 2.1 from page 24 of the Report):

‘Integrating climate considerations cases’ (the largest category of cases to date both inside and outside the US): litigation that aims to integrate climate considerations, standards or principles into a policy or decision, with the dual goal of stopping the harmful policy or project while also mainstreaming climate concerns in policy-making;

‘Government framework cases’: litigation that challenges the ambition or implementation of a government’s climate target and/or policies;

‘Polluter pays cases’: litigation that seeks monetary compensation from (generally, private sector) defendants based on their alleged contribution to harmful impacts of climate change;

‘Corporate framework cases’: litigation that aims to disincentivise companies from pursuing high-emitting activities by requiring changes in group-level policies, corporate governance and decision-making processes;

‘Failure to adapt cases’: litigation that challenges a government or company for failure to take climate risk into account;

‘Turning off the taps cases’: litigation that challenges the financing of projects and activities that are not aligned with climate action;

‘Climate-washing cases’: litigation that challenges inaccurate government or corporate narratives regarding contributions to the transition to a low-carbon future; and

‘Transition risk cases’: this category of strategic litigation has been introduced by the Report this year and refers to litigation concerning the (mis)management of transition risk by directors, officers and others in similar positions responsible for ensuring a business’ success (previously referred to as 'personal responsibility' cases).

The last two categories of emerging strategic cases are particularly relevant.

'Climate-washing cases' are one of the most rapidly expanding areas of climate litigation, with 140 cases filed to date. These cases are increasingly being initiated against companies, focusing on the credibility of climate commitments and investments in or support for climate action, product-specific challenges (including the use of certain terms like net zero, climate neutrality, and deforestation-free) and can involve financial products and services. Such challenges have been successful in 54 of the 77 decided cases to date, and these include investigations by regulators (including ASIC v Vanguard Investments Australia Ltd - see our Knowledge Insight here) and complaints before quasi-judicial bodies (e.g. advertising standard boards).

However, the Report questions the extent to which such cases directly contribute to a reduction in carbon emissions and/or achieve substantive climate action goals. Arguably this kind of climate-washing litigation contributes more indirectly, serving as a deterrent against misleading practices and reinforces the importance of transparency and accountability in achieving meaningful progress towards global climate objectives.

Transition risk cases include the following:

Arguably the most famous example of this is the case brought in 2023 by ClientEarth against the Shell Board of Directors for failure to implement policies that would enable it to meet its net zero commitment (ClientEarth v. Shell Board of Directors). This case was dismissed by the UK High Court in the same year although it is very likely that the issues raised in this case, including about prudent climate risk management, will be put before the court (in the UK or elsewhere) again without undue delay.

The Report also points to the French case of Mtamorphose v. TotalEnergies filed in 2023. In that case, shareholders sued Total Energies for allegedly unlawfully distributing dividends on the basis that the company had not adequately accounted for the depreciation of its assets due to the increasing cost of carbon and did not consider the impacts of its Scope 3 emissions.

The decision in December 2023 by the Polish energy company Enea to sue its former directors (and insurers) who had supported the company’s investments into an (ultimately cancelled) coal-fired power station project (Project ). The case focuses on a lack of due diligence around the financial implications and potential stranded asset risk of constructing the Project in 2018 (and follows a successful case brought against Enea in 2019 by ClientEarth seeking to nullify the company resolution consenting to the Project).

The outcome of these cases will be closely watched to inform the broader European context of these issues which the Report expects will increasingly be litigated by stakeholders.

Historically, cases against companies have mainly targeted the fossil fuel sector, but the Report notes that this is increasingly diversifying. The airline sector received particular attention in 2023. Other sectors now firmly in focus and facing legal challenges about climate include the food and beverage sector, e-commerce and financial services, with many of these cases looking to target the services that enable the work of fossil fuel companies (e.g. financial services, consultants etc) categorised (as referenced above) as 'turning off the taps' litigation). The Report also notes that the focus is turning to harm caused by deforestation, animal agriculture and the associated food and beverage supply chains, which will be of particular importance in Australia.

Human-rights-based arguments and the role of international courts and tribunals

Although cases brought before international courts make up only 5% (146) of the total number of climate cases, many of these cases have received a significant amount of attention, with the potential to influence domestic proceedings. Further, almost half of these cases (45%) have been filed before international human rights courts, bodies or tribunals, demonstrating the increasingly prevalent role that human rights arguments are playing in climate-related litigation.

In 2023, two requests were submitted for advisory opinions on climate change issues; a request to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and a request to the International Court of Justice (with opinions expected in late 2024 and early 2025 respectively). May 2024 saw the publication of the first climate change advisory opinion issued by the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (the request was made in 2022). This clarified that states have specific obligations to prevent, reduce and control pollution, including greenhouse gas emissions, and their detrimental effects on the marine environment (see our detailed Knowledge Insight here).

Although these advisory opinions are non-binding, the Report notes that the significant state and general public engagement with these proceedings appears to illustrate “global concern and interest in clarifying state obligations regarding climate protection” and the decisions will likely be used as “building blocks for further litigation” before both international and national courts (see page 15 of the Report).

The European Court of Human Rights decision in April 2024 in the case of KlimaSeniorinnen and Ors. v. Switzerland , which confirmed that government failure to act on climate change constitutes a violation of the European Convention on Human Rights was a particularly important finding (for an overview of this case, see our Knowledge Insight here ) and arguably set a precedent for national and international courts in interpreting the human rights obligations of states regarding climate action. The fact that this case was handed down by the ECtHR at the same time as two others ( Carme v. France and Duarte Agostinho and Others v. Portugal and 32 Others) also raised awareness of the issues considered by the ECtHR.

The Report also notes that in certain jurisdictions, where rights-based legal actions are less available, alternative strategies have been adopted to make similar arguments. This has been the case in Australia, where rights-based legal actions are constrained in both availability and scope, largely due to the absence of an established human rights framework. The Report refers by way of example to the case of Pabai Pabai v. Commonwealth of Australia . In that case, First Nations leaders from the Torres Strait Islands challenged the Australian government’s failure to cut greenhouse gas emissions, asserting that the government’s inaction would force their communities to migrate to new areas. The claims are grounded in tort law (rather than any human rights law) - specifically, that the Australian government owes a duty of care to Torres Strait Islanders to take reasonable steps to protect their communities and environment from the adverse effects of climate change, and that the government has breached this duty by failing to set targets that are consistent with the best available science.

Non-climate-aligned litigation

While the majority of climate cases recorded are cases that seek to hold governments and corporations accountable for inadequate action in tackling the climate crisis, courts are also being used as a venue for advancing agendas that are not aligned with climate goals, referred to in the Report as 'non-climate-aligned cases'.

The majority of non-climate-aligned cases have been filed in the US. In particular, the Report refers to 'ESG backlash' cases, where claimants have been targeted specifically because they were engaging in climate-aligned action and in a jurisdiction where ESG investment practices can be seen to be political. For example, the Report notes that in 2023, there were significant cases using consumer protection law (e.g. State ex rel. Skrmetti v. BlackRock, Inc. , where the plaintiff alleges consumer confusion over BlackRock’s simultaneous pursuit of maximising investment returns and minimising environmental impact) or alleging breaches of fiduciary duties related to the integration of climate risk into financial decisions (including Spence v. American Airlines ) .

Further, the Report notes that recent cases in the US focusing on climate-related financial risk have largely been non-climate-aligned, which contrasts with the prevailing trend globally. The Report questions the extent to which this may indicate the direction of things to come in the rest of the world (on the basis that US litigation can set a precedent for strategies adopted globally), albeit noting that the particular political dynamic in this instance may be specific to the US.

Although relatively few in number, it is important to note the presence of SLAPP suits. These are cases brought against those advocating for climate change and the environment. The Report notes that, in general, the objective of these cases is to “intimidate and silence the target of the SLAPP while exhausting their resources”, as opposed to obtaining redress, and that SLAPP suits are “frequently an abuse of the legal process that involves expensive and meritless litigation” that can be used to “harass an opponent and prevent climate activism and public participation”. The Report refers to the cases filed in the UK (by Shell ) and France (by Total ) against Greenpeace and other NGOs in response to climate-aligned action taken by those NGOs. By way of further example, in January 2024, Exxon filed a claim against two shareholder organisations (Arjuna and Follow This) to prevent a shareholder resolution those two groups had sponsored urging Exxon to adopt a more rapid emissions reduction trajectory from appearing on the agenda of Exxon’s annual meeting. The resolution was withdrawn after the complaint was first filed.

Although not specifically referred to in the Report, we note that in Australia, where SLAPP suits have not been common, litigation is evolving, and we have recently seen an example of a corporation pursuing cost recovery from an environmental charity (whose case against the corporation failed). Following the Federal Court of Australia’s judgment in Munkara v Santos NA Barossa Pty Ltd in January 2024, where the Court rejected claims by the Tiwi Islander applicants that Santos’ proposed Barossa pipeline would damage sea country, Santos confirmed that it would not pursue costs against the Tiwi Islander applicants. Instead, however, Santos has subpoenaed documents from the applicants’ legal representatives, the publicly funded Environmental Defenders Office (EDO), and other environmental charities, to look to identify the funding sources of the EDO and to potentially substantiate a case for costs against the EDO.

Santos alleges that the EDO’s behaviour during the litigation, particularly in relation to the preparation of evidence, was improper and should warrant “cost consequences” for the lawyers. Although the Court’s judgment noted some concern about the credibility of EDO’s evidence, if granted, this sort of cost order could deplete environmental organisations and threaten the viability of future public interest cases.

Although not straight-forward anti-climate action per se, the Report also points to the increasing number of cases challenging the way in which climate action is being taken and how actions taken to address the climate crisis have been designed, including 'just transition' cases, where claimants are challenging the balance struck between advancing climate action and the rights of affected communities, for example in Chile, France and Pakistan.

The Report also refers in this context to the emergence of 'green v green' litigation, that is, cases where climate and biodiversity or other environmental aims are competing. Again, these cases are not anti-climate action, rather they are about the need to balance climate action with other conservation measures.

Future trends and impacts of climate litigation

The Report anticipates that future trends will include cases challenging recovery efforts made after climate disasters, the application of criminal law and the emerging concept of 'ecocide' and the convergence of environmental issues (e.g. plastic pollution), climate litigation and human rights.

In particular, in relation to the concept of 'ecocide', the Report notes that efforts have already been made to involve the International Criminal Court in climate issues, including most recently in a letter issued by the World Council of Churches to the Assembly of State Parties to the International Criminal Court arguing that the Rome Statute (the foundational treaty establishing the Court) should be amended to include crimes relating to climate disinformation promoted by corporate actors.

The Report also notes the focus on the concept of extended producer responsibility and the increase in laws and policies requiring producers to take responsibility for the entire lifecycle of their products, including disposal and recycling. The ongoing developments of a plastic treaty will be a major step towards reducing emissions from plastic production, use and disposal, and as public and legal scrutiny of the environmental harm of plastic increases, we are likely to see plastic litigation more squarely within the frame of climate litigation.

Human rights are also expected to increasingly intersect with, be influenced by, and inform climate litigation. For example, in March 2024, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) held a state responsible for violating the right to a healthy environment in The Community of La Oroya v Peru . The IACHR held that the government of Peru had breached its obligation to protect the residents of La Oroya’s right to a healthy environment by failing to protect the community from toxic pollution from a private lead smelter. The IACHR ordered the State of Peru to adopt comprehensive reparation measures for the damage caused to the population of La Oroya. As noted above, an advisory opinion in respect of states’ climate change obligations is also pending from the IACHR and is expected to be issued later this year.

The Report contends that the growing constellation of climate litigation impacts, and of course is impacted by, public discourse, climate policy, legislative reform, the action of central banks and financial regulators, the insurance sector and the broader legal profession. The Report powerfully concludes that “[u]nderstanding the nuance and scope of these changes remains an urgent challenge”, but one that will influence the governance of climate change more broadly.