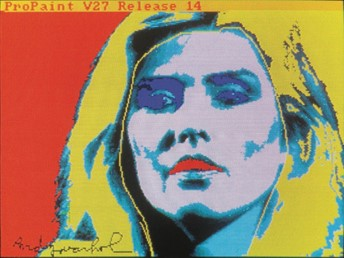

In 1985, before a live audience at the launch of Commodore’s Amiga computer, Andy Warhol used the computer to create a screen print-like multi-coloured image of Blondie singer, Deborah Harry, from a monochrome photo of her.

If Warhol was alive today and used AI instead to create the image, would it be copyrightable?

As the US Copyright Office observes in a recent report, the history of copyright law has been one of gradual expansion in the types of works given protection. So, have we reached this point with AI-generated content? The Office says that the answer depends on the specific case.

Pre-AI computer Art

Creators have used computer-assisted technology for decades to enhance, modify and add to their creations – without jeopardising the availability of copyright protection for the work as a whole.

The first computer generated ‘art’ apparently was a rendering of a female model using a US military computer in 1956.

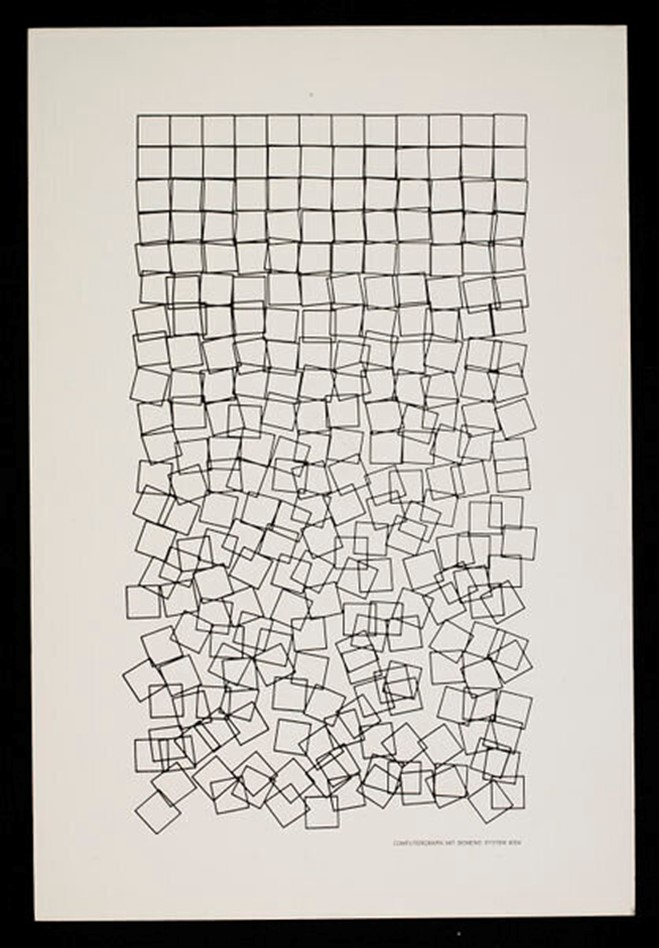

Georg Nees is considered one of the founders of computer art. He used a 'Zuse Graphomat', a drawing machine operated by computer-generated punched tape. He generated the following image by shuffling random variables into the deck of punch cards, causing the orderly squares to descend into chaos.

At the 1968 Cybernetic Serendipity computer art exhibition in London, Jean Tinguely displayed his machine which painted pictures:

In the 1970s, Xerox released the Graphic User Interface for computers, popularised by the first MacIntosh computer released in 1984. The use of computers as an artist tool took off.

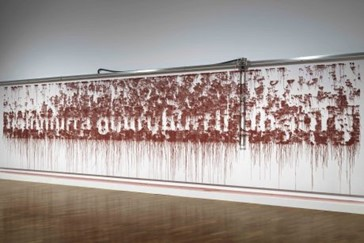

Recently, Australian artist Rob Andrews, a Yawuru man, has built a writing machine employing open-source, programmable technologies, which slowly exposes words in the language of the Traditional Custodians of the Kamberri/Canberra region on an ochre-painted wall by eroding the outer layer of white chalk.

Only humans can be creators under current law

US courts have consistently rejected copyright in material created by non-humans: in two famous cases, drawings allegedly by ‘human spirit beings’ and by monkeys. Therefore, copyright only protects works of human creation.

On the other hand, a century ago, the US Supreme Court rejected an argument that photographs were not copyrightable as the products of a machine. The Court considered there was still sufficient human creativity behind the lens, photographer, including “posing the [subject] in front of the camera” and “evoking the desired expression”.

In 1965, the US Copyright Office ruled:

The crucial question appears to be whether the ‘work’ is basically one of human authorship, with the computer merely being an assisting instrument, or whether the traditional elements of authorship in the work (literary, artistic or musical expression or elements of selection, arrangement, etc.) were actually conceived and executed not by man but by a machine.

What sets generative AI apart is that, with minimal human involvement – such as a prompt, AI can produce an ‘original’ artwork, song or design: for example, prompting for “a rock punk song about my dog eating my homework” on Suno.

When is AI the tool and when is AI the author?

The question then is whether AI is being used as a tool to assist in the creation of works or as a stand-in for human creativity. The US Copyright Office thought the answer depended on how the AI system is being used and not on its inherent characteristics.

The US Copyright Office concluded that, given current generally available technology, prompts alone do not provide sufficient human control to make users of an AI system the authors of the output. Prompts essentially function as instructions that convey unprotectible ideas – even where containing a fairly detailed specification of the user’s desired expressive elements.

To use a real-world analogy, a person commissioning a work will not be considered the sole or joint author of the work unless the process of producing it is automatic or a mechanical transcription. However, with AI:

Although AI technology continues to advance, uncertainty around how a particular prompt or other input will influence the output may be inherent in complex AI systems built on models with billions of parameters… many popular AI systems are unpredictable in the sense that their outputs may vary from request to request, even with an identical prompt.

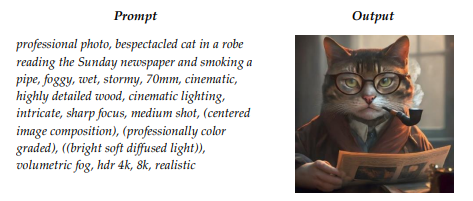

The US Copyright Office illustrates the gaps between prompts and AI output by the following:

While faithfully reflecting some of the prompt detail (the pipe smoking), the AI ignored other elements (the panelled wood setting), filled in other details on its own (the breed of cat) and ‘freelanced’ on others such as using a human hand rather than a paw to hold the newspaper.

Some submitters had argued that a degree of randomness can be present in artistic works, such as how the paint flicked by Jackson Pollock hit the canvas. However, the US Copyright Office rejected this analogy:

Jackson Pollock’s process of creation did not end with his vision of a work. He controlled the choice of colours, number of layers, depth of texture, placement of each addition to the overall composition – and used his own body movements to execute each of these choices.

The US Copyright Office considered that copyright could apply to an AI output if the prompt contained expressive elements, the AI was being prompted to modify or augment it and the human-authored inputs are sufficiently reflected in the output, as demonstrated in the following:

But the Office also noted that the applicant expressly disclaimed “any non-human expression” appearing in the final work, such as the realistic, three-dimensional representation of the nose, lips and rosebuds, as well as the lighting and shadows in the background.

Conversely, where a human takes AI generated images and selects or arranges them in a sufficiently creative way, the resulting work will constitute an original work of authorship (but not the AI generated images alone).

Should the law be changed to protect AI-generated content?

Some submitters argued that extending copyright law or enacting sui generis protection (an AI specific IP law) to cover AI-generated content would incentivise creation of more content and the building of sophisticated AI ‘authors’, which would be consistent with the spirit of copyright law. However, the US Copyright Office took the opposite view:

Inanimate objects don’t need incentives to create – they do what they are programmed or developed to do.

If a flood of easily and rapidly AI-generated content drowns out human authored works in the marketplace, additional legal protection would undermine rather than advance the goals of the copyright system. Universal Music Group submitted that already “content oversupply” produced by an estimated 170 million AI-generated music tracks, currently threatens to dilute human creators’ royalties.

The US Copyright Office acknowledged that AI opened opportunities for artists with disability to produce content not otherwise possible for them. However, the Office thought that while creators with disability may lean more heavily on AI, it still was being used as a tool within the current copyright paradigm, and it gave the following example:

The Office recently considered an application to register a sound recording by GRAMMY-winning country artist Randy Travis, who has limited speech function following a stroke. The track was created based on the recording of a human voice, using “[a] special-purpose AI vocal model . . . as a tool . . . to help realise the sounds that Mr. Travis and the other members of the human creative team desired.” The result, which would have been infeasible without this technology, was a new track appearing to be sung in Travis’s legendary voice. Because the sound recording used AI as a tool, not to generate expression, the Office registered the work.

Some submitters, while supporting the requirement for human authorship, called for copyright law to be clarified as to the extent of copyright protection afforded to works created with assistance from AI. Creative industry stakeholders in Australia made similar submissions to the Parliamentary Select Committee inquiry on AI.

However, the Copyright Office rejected the need for any change:

Current law was sufficiently flexible to incrementally evolve to accommodate assistive use of AI by creators, including with the greater clarity this report brings.

If there was to be a change in the law, there is no consensus around which human should hold the copyright – some argue the developers of the AI system while others argue for the user writing the prompt.

Conclusion

Like those early innovators of computer art, many artists are intrigued by the possibilities of AI, beyond the characterisation of AI as a tool. Mixed-media artist Matt Sanders:

I am sure many artists will be intrigued by the “agency” of AI and seek ways to grapple or collaborate with it. Many already are. And we should be grateful to be challenged and knocked out of our habits and assumptions!

Independent animator Ruth Stella Lingford:

Although it is maybe far-fetched to talk about AI as creative or imaginative, the melding of images from different sources, with large elements of the random, closely approximates some aspects of the creative process. AI is acting like a sort of collective unconscious, and I do find some of what it produces very interesting.

Peter Waters

Consultant