Most adults have experienced ‘technology humiliation’ at the hands of a toddler armed with a remote control. Will children be so adaptive to AI, and what impact will AI have on their development?

Two recent studies have tried to fill the empirical gap on the impact of AI on children - by asking children themselves.

A Dutch study surveyed 374 children, mainly primary schoolers. A Scottish study, jointly undertaken by the Scottish Children’s Parliament and the Alan Turning Institute, surveyed 87 members of the Children’s Parliament and worked in-depth with 13 children as ‘investigators’.

What is different about AI for children?

The Dutch study identified three special aspects of a ‘child’s eye’ view of AI:

the Stanford University Global AI Index found that adult humans are only able to accurately distinguish between AI-generated and human-made text up to 50% of the time. What chance do children have, at much earlier stages in their cognitive development?

research shows that children's interactions with robots compared to adults are more complex because children anthropomorphize robots through "pretend play".

on the positive side, children possess a ‘unique human-centric lens’ because they have not yet mastered (or been limited by) the social norms which guide adults. Children may be able to teach us a lot about how humans and AI should ideally interact.

Your children probably are already daily users of AI

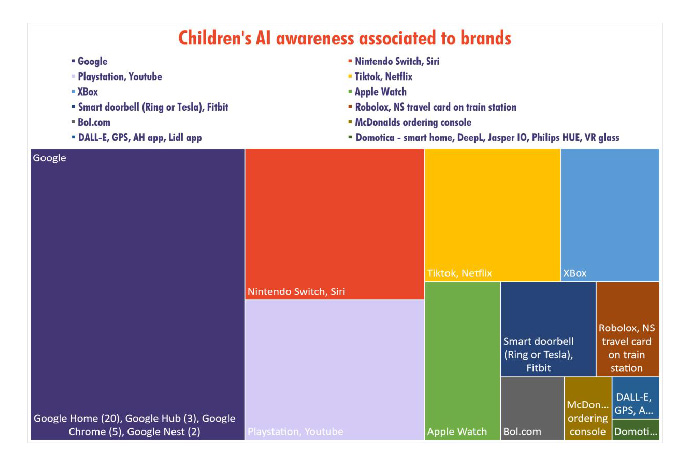

In the Dutch survey 70% of the surveyed children said that they had never heard of AI but, all participating children were able to list a broad variety of AI systems, mainly by brand name or device name.

Children’s exposure to AI is rapidly increasing. The Dutch study notes that “although the surveys were taken between July and the end of October 2022, and the large language model-based DALL-E just appeared as a novel innovation towards the end of this period, it is remarkable that some young children have already recognized these AI systems.”

The Scottish survey found that children are familiar with the concept of AI being a part of their everyday lives but do not necessarily understand the detail of where and how it is used. As with the Dutch survey, most children could identify in their daily lives devices or apps which use AI. Fairly typical of the responses, an 8 year old from Shetland Islands said:

“Yeah, I’m feeling positive about AI. I am excited to learn more because I am not sure about it, I think it is on my phone. I want to learn more about the inner workings of it.”

while more amusingly a 10 year old from Edinburgh gave this example:

“Is the school bell AI? I think it probably is!”

‘What if’ scenarios

The Dutch study asked how they would react to use of AI in 6 scenarios: a robot as a seller, a robot as a police agent, a robot as a GP, a robot as a nanny, a driverless car, and a robot friend. As a taste of the children's response on some of these scenarios:

Robot Seller

When asked whether they would want to be assisted by robot sellers in shops: 55% of children said ‘yes’ and 41% said ‘no’. Most of those in favour of robot sellers said that this would be ‘cool’ or that robots would be more efficient than humans.

Those that said ‘no’ mainly gave as their reason the lack of human interaction. Some expressed concerns about the social impact of robot sellers:

"No, because almost every seller could lose their job and you cannot really chat nicely with a robot and real people are really much nicer." (7 years old girl).

Interestingly, in the other 5 scenarios, the majority of children flipped to being uncomfortable with use of AI/robots.

Robot GP

62% of children said they would be uncomfortable being assisted by a robot general practitioner while only 35% were positive about the idea.

The main concern with robot GPs again was the robot’s lack of human qualities, sometimes with a funny twist on the anxieties about being treated by a machine:

"A robot GP could transmit electricity when it touches me and a human doctor does not do that." (8 year old boy)

The minority who favoured robot GPs thought they could outperform humans in diagnosis and treatment.

Robot Nanny

In the case of a robot nanny, 59% of children did not want and 37% wanted to be assisted by a robot nanny while being home alone.

Some of the positive reasons given included that the child thought the robot nanny would be less strict or the child would have more control:

"Yes, it “Yes, it would be super fun! If it was poorly programmed, it could say yes to everything like going to McDonald's." (8 year old boy)

For those opposed to a robot nanny, the lack of human interaction was the main reason. Some thought robot nannies would be harder to win over and therefore would be stricter.

Robot as a friend

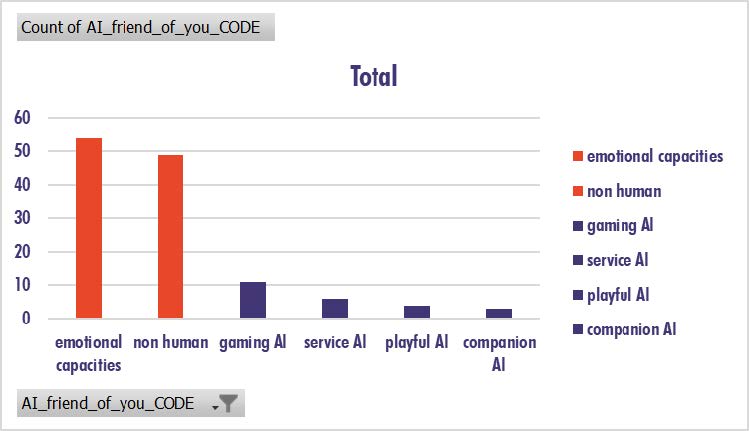

Concerns about the loss of the human dimension was strongest when children were asked to image whether a robot could be their friend, as the table below shows (red is negative and blue is positive reasons).

Some typical responses were:

"No, I would rather befriend real living persons, there are plenty of them on this planet." (11 year old, girl)

"If robots could get humour and feelings then it could be possible." (12 years old boy)

Good vs bad AI

The children in both studies study were asked about the use of AI in their education. A 10 year old girl in the Dutch study said:

"An AI could help with extra schoolwork at school. I have dyslexia and it would be nice if there was extra help for that with today's teacher shortage." (10 year old girl, primary school)

Children in the Scottish study also thought felt educational AI could be very useful, but worried about what might happen if it was relied on too heavily: a 10 year old from Shetland said:

“If AI was teaching most of the people in schools and like all that, then they wouldn’t actually get much opportunity to hear an actual person saying it; it would just be, like, a robot saying all their subjects all the time. And it would probably be a bit frustrating because the robots know everything, and the teachers learn new things through the children.”

Children in both studies expressed concerns about the impact of AI on their privacy:

"I prefer to rely on people (human for me) and not on AI because of the big corporations and their algorithms, see TikTok, for instance." (8 year old boy in the Dutch study)

“There’s also some issues like there could be companies getting information about you and making it more tempting to do stuff like spending money and it’s not going to be good for children because they might spend money accidentally.” (10 year old in the Scottish study)

Children in both studies expressed the hope that AI could help solve the climate change crisis.

AI with children in mind

The primary objective of the Dutch study was to identify, through the eyes of children, principles which should guide how AI should be designed “in those ‘small places’ where children gather their first interactive experiences in their lives”. The study did this by synthesising from the children’s response a set of ‘values’ important to children:

“Each value in this section is considered to be sustainably important to uphold by children when living with AI systems and humans in society. Based on these grounds the eight values inducted from children's responses when living in an AI-mediated society were the following: human literacy, emotional intelligence, love and kindness, authenticity, human care and protection, autonomy, AI in servitude, and exuberance.”

Some of the representative comments from children under each of these values were as follows:

Human literacy:

"If a robot was made to be my friend and would only learn from me that robot would only be able to replicate what I do? How could I know how to make others happy or what is sad? How can I learn and adapt to others' needs and moods, if I would only learn from a robot friend what I am doing?" (8 year old girl)

Emotional intelligence:

"Real people, I find still more social. A robot would not be able to help, if I had a quarrel with my sister." (10 year old girl)

Love and kindness:

"If you want to be my friend you would need to be able to be loving and kind and a robot cannot do that." (11 year old boy)

"For me the best robot would be a mini Minecraft robot that I could take into my pocket and that would guide me how to stay on a good path and do the right things." (8 year old boy)

Authenticity:

"I think AI systems are unable to express their own opinions, they simply cannot. They always express the opinions of others." (11 year old)

Human care and protection:

"I wouldn't like it if I was driven by a self-driving car because they can't talk nicely and don't know how you feel before a competition. Your mother, for example, does know because that's your mother..." (11year old girl)

Autonomy:

"I do not want robots to take over the world." (10 year old girl)

Serving humans

"My best robot would be an Octopus that would work between 7:30 and 8:30 the hardest with his or her 8 hands so that my parents would have more time for me." (11 year old girl)

Exuberance

"A robot that can play with me outside and can also play a game with me inside." (8 year old boy)

"Not social, not personal, you cannot laugh with a robot and cannot converse like with peers." (9 year old girl)

The results of the Scottish study also reflected the ‘unique human-centric lens’ which children can bring to AI. The researchers found that, as children’s knowledge of AI increased over the course of the project, they expressed concern about its potential negative impact on people and society:

“Sometimes AI can go wrong where it can go maybe like sometimes racist or even just give you the wrong stuff.” (10 year old from Glasgow)

“It could recognise criminals, but it could also recognise people who weren’t criminals. So if we trained it not to look at people who weren’t criminals, the people could have a better life.” (10 year old from Stirling)

Conclusions

The Dutch study drew three conclusions:

children give over-riding importance to human values when they were triggered to think of situations involving interactions with AI which are potentially void of these. For example, “the need for human literacy by children emerged from imagining the possibility that human traits would no longer be recognizable and distinguishable by children when they would interact with robots.”

children will grow (emotionally, physically, socially) as humans when interacting with AI systems but AI systems do not (i.e. as synthetic system): therefore “[t]aking a broad diversity of child perspectives into account when designing .. AI systems..is key in order to assess what the meaningfulness of these systems in children's lives are and how they influence how children (should) grow.”

Children have something to bring to how we design and use AI. “[a]llowing children to carry out thought experiments and share their sentiments about current AI systems and their future vision is useful to cultivate their skills needed in the 21st century: creative expression, critical thinking, public speech and debate, creative collaboration.” But even more broadly, viewing AI through children’s “unique human-centric lens” could create new perspectives on AI and its use in society.

The Scottish research formed the basis of a children’s rights session run by the child investigators at a March 2023 Scottish AI industry conference. The researchers reported that the adult attendees were ‘captivated’ by the children’s perspectives on AI:

“Thank you for sharing your ideas with the adults here. I hope more people will think about children’s rights when they are designing AI now. You answered so many difficult and emotional questions on AI and have inspired me to make sure that in my work, I involve many different children in planning my research.”

Read more:

Exploring Children’s Rights and AI

Peter Waters

Consultant