On 8 July 2024, the ACCC published a draft guide on sustainability collaborations and Australian competition law (Draft Guide) for consultation.

As we noted here , consumer, product safety and competition concerns in relation to environmental claims and sustainability continue to be an ACCC compliance and enforcement priority.

While previous guidance has related to consumer law aspects such as greenwashing, the Draft Guide focuses on competition - specifically, ' sustainability collaborations' , which the ACCC defines as discussions, agreements or other practices amongst businesses aimed at preventing, reducing or mitigating the adverse impact that economic activities have on the environment.

According to the ACCC’s media release , the Draft Guide:

provides guidance for businesses on the competition law risks that may arise in relation to sustainability collaborations under the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (Act ); and

explains how exemptions from competition law through the ACCC authorisation process may be available for sustainability collaborations that are in the public interest.

It includes practical tips for applying for authorisation, as well as a number of both historical examples and hypothetical case studies, providing more concrete guidance for businesses as to best practice.

Unlike the guidance on sustainability agreements published by the Netherland Authority for Consumers and Markets in October 2023, but similar to the New Zealand Commerce Commission’s guidance on collaboration and sustainability published in November 2023, the ACCC has not undertaken not to take action for certain types of sustainability collaborations that might otherwise breach the law. Rather, the ACCC has reiterated the importance of seeking authorisation where certain risks arise before engaging in conduct that may otherwise breach the Act - only then will businesses be entitled to engage in that conduct without risk of the ACCC, or third parties, taking legal action against them for breaches of the Act.

Competition law risks of sustainability collaborations

Sustainability collaborations may amount to:

cartel conduct (where two businesses that compete for the supply or acquisition of goods or services agree to act together, rather than competing), including where:

businesses that compete to acquire certain types of input agree to only buy the inputs from suppliers that meet particular sustainability criteria;

suppliers agree to charge levies on the sale of their products to customers, in order to fund industry recycling schemes for products at the end of life; or

rival manufacturers agree to use new technologies in their production processes and stop using older technologies that emit more pollution; or

other contracts, arrangements or understandings, or concerted practices, or exclusive dealing, which have the purpose, effect, or likely effect of substantially lessening competition (SLC ) - some factors affecting whether sustainability collaborations are likely to have the effect of SLC are set out in the table below:

| More Likely | Less Likely |

| Prevents businesses from competing effectively.Makes it more difficult for new businesses to start competing or makes it hard for existing businesses to expand.Involves the sharing of commercially sensitive information, particularly price-sensitive information. | The businesses are not competitors in terms of selling or buying goods or services.The businesses are making decisions independently, rather than in consultation, coordination, or cooperation with competitors.The businesses are free to innovate, buy from or sell to whom they choose.It does not involve the sharing of commercially sensitive information, particularly price-sensitive information. |

More Likely

Less Likely

Prevents businesses from competing effectively.

Makes it more difficult for new businesses to start competing or makes it hard for existing businesses to expand.

Involves the sharing of commercially sensitive information, particularly price-sensitive information.

The businesses are not competitors in terms of selling or buying goods or services.

The businesses are making decisions independently, rather than in consultation, coordination, or cooperation with competitors.

The businesses are free to innovate, buy from or sell to whom they choose.

It does not involve the sharing of commercially sensitive information, particularly price-sensitive information.

The ACCC has provided the following examples of low-risk sustainability collaborations:

jointly funded research into reducing environmental impact;

pooling information about the environmental sustainability credentials of suppliers;

industry-wide emissions reduction targets; and

independent decisions about using sustainable inputs.

The authorisation process

Authorisation exempts recipients from the competition provisions of the Act, with environmental and sustainability benefits being public benefits the ACCC may take into account in assessing authorisation applications.

In the media release accompanying the Draft Guide, ACCC Acting Chair Mick Keogh said:

We have a clear legal mandate to take sustainability benefits into account when considering how best to promote competition and advance the interests of consumers. Our intention in developing this guide is to make it clear competition law should not be seen as an immovable obstacle for collaboration on sustainability that can have a public benefit.

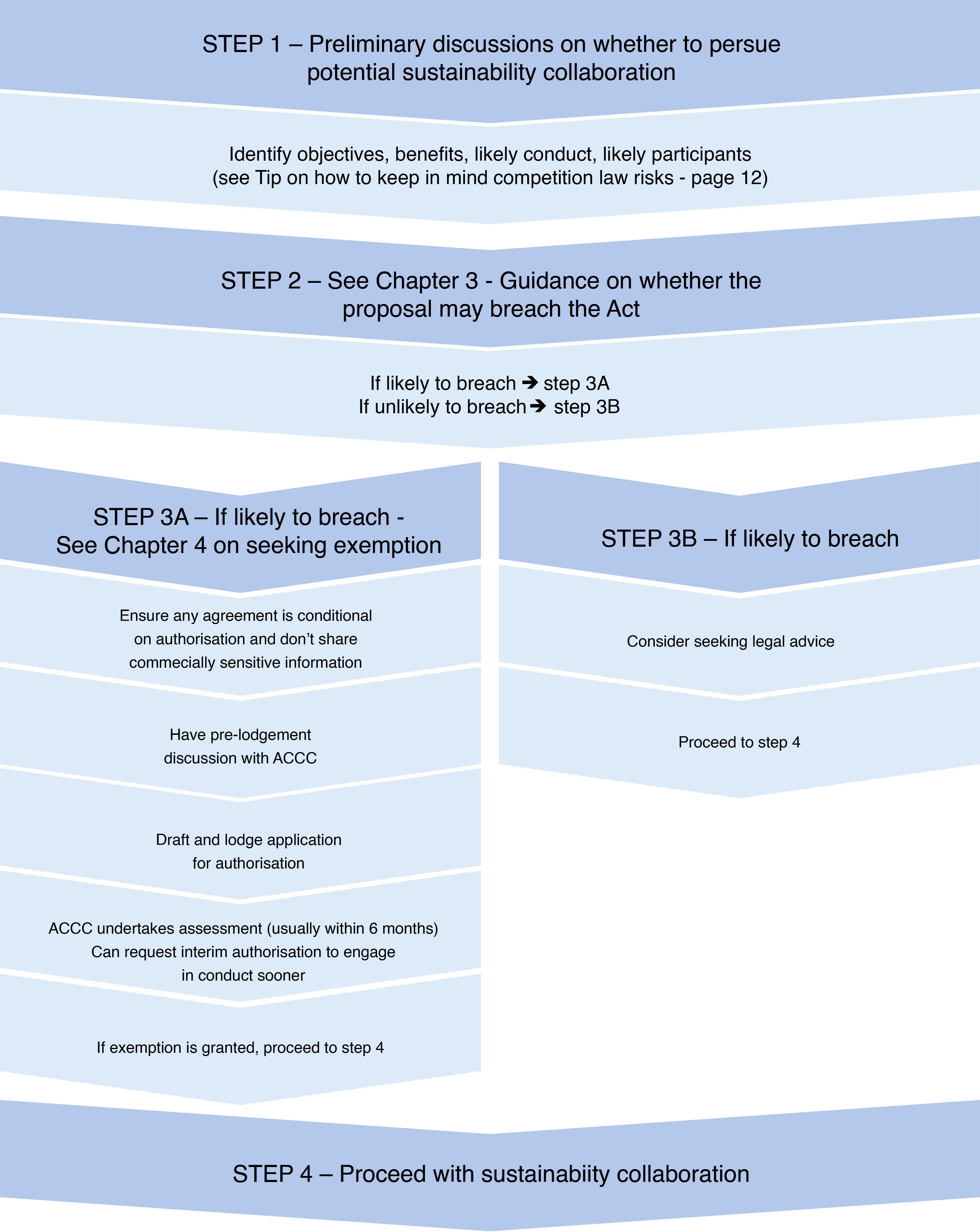

The ACCC considers that businesses should undertake the following steps when considering a potential sustainability collaboration:

In seeking authorisation, the proposed conduct must be described in a sufficiently precise manner to allow the ACCC to consult with interested parties and assess the application. Further, the provisions of the Act for which authorisation is sought must also be specified.

For collaborations which may breach the prohibitions on cartel conduct, the ACCC may grant authorisation if it is satisfied that the likely public benefit resulting from the proposed collaboration outweighs the likely public detriment (that is, results in a net public benefit). Authorisation on competition grounds is not feasible due to the prohibitions on cartel conduct being per se prohibitions.

For collaborations which may breach the other prohibitions on anti-competitive practices involving SLC, the ACCC may grant authorisation if it is satisfied that the collaboration would either:

not have the effect or likely effect of SLC; or

result in a net public benefit.

Preliminary discussions and feedback

In the Draft Guide, the ACCC emphasises that it is available and willing to engage with businesses about potential applications for authorisation for sustainability collaborations.

In approaching the ACCC for preliminary discussions, businesses should identify:

the objectives and public benefits sought to be achieved;

any features that might limit the impacts on competition; and

the businesses who are intended to be part of the collaboration.

The ACCC can then provide guidance on:

the suitability of the exemption process, as compared to other avenues;

the factors to which it will have regard in assessing the application and explain in general terms the issues that should be addressed in the application;

information it might need; and

steps in the process and likely timeframes.

Further, the ACCC can also review draft applications and:

provide feedback on potential areas of concern; and

indicate where more information or justification is needed.

Public benefits and detriments

The ACCC considers that public benefits may arise from:

mitigation of market failures, including where:

providing a good or service has a social cost greater than the cost to the purchaser (for example, where the product price does not include the eventual cost of recycling at the end of the product’s life);

acting individually, a business considering a switch to a more sustainable but expensive input may be at a competitive disadvantage relative to other businesses that do not make the switch (i.e. a first mover disadvantage); and

an individual business lacks the resources and capabilities to achieve environmentally sustainable outcomes, but a group of businesses could act collectively, for example:to set up a stewardship scheme to fund recycling and disposal activities or facilitate research and development to identify new markets for end-of-life products; and/orto establish the scale required to make a project commercially or technologically feasible; and

to set up a stewardship scheme to fund recycling and disposal activities or facilitate research and development to identify new markets for end-of-life products; and/or

to establish the scale required to make a project commercially or technologically feasible; and

to set up a stewardship scheme to fund recycling and disposal activities or facilitate research and development to identify new markets for end-of-life products; and/or

to establish the scale required to make a project commercially or technologically feasible; and

creation of positive externalities, such as where the financial benefit that a firm might receive from acting individually might not be sufficient for it to justify the investment required to give rise to the environmental benefit, but an authorisation enabling firms to share the relevant cost may give rise to the requisite investment.

Some specific types of sustainability benefits that the ACCC may take into account include:

reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (expressly stated to have been accepted as a public benefit of considerable weight);

biodiversity conservation;

reduced plastic use; and

increased circularity.

These public benefits do not need to flow back to the consumers directly impacted by the conduct, so long as they accrue to society generally.

The ACCC provides the following tips for making public benefit claims to support authorisation:

Outline the public benefits claimed to arise from the proposed collaboration . This includes identifying why the public benefit will not exist or will exist only in part, without collaboration.

Identify why the public benefits claimed are likely to result - that is, why the benefits are not mere possibilities, and there is a real likelihood of them occurring.

Provide evidence that supports the public benefit claims. Claims should be clear, specific, and avoid using vague language.

Where possible, quantify the size of the likely public benefits (and public detriments) . For example, it may be necessary to estimate the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions arising from a proposed authorisation. Then, if possible, parties should attempt to fix a dollar amount for the value of that public benefit. An explanation of any methodologies, assumptions and sensitivity testing used in the quantification should also be provided.

Outline why the proposed collaboration is required to achieve public benefits and why businesses cannot individually address the sustainability concern.

Outline why the proposed collaboration is proportionate. Parties should try to demonstrate that the collaboration is no more restrictive on competition than is reasonably necessary to achieve the relevant benefits. There should be a ‘net public benefit’ that outweighs any adverse impact on competition.

Where relevant, include the domestic or international standards that the proposed collaboration is designed to achieve or exceed. If technical standards are being developed, include the research and/or scientific method that the technical standards are based on.

Explain what, if any, transparency and reporting measures are included to ensure that the public benefits are achieved, including if there are steps in place to identify and address any issues.

The primary public detriments with which the ACCC is concerned are those flowing from the lessening of competition, which may be limited where:

they impact only a limited aspect of how the businesses involved compete with one another;

the participants collectively have only a small market share (whether by supply or acquisition);

only information necessary for businesses to perform the relevant conduct is shared, reducing the potential for coordinated conduct;

incentives remain for individual businesses to achieve sustainability outcomes over and above the proposed collaborations;

the collaboration does not create or enhance the market power of participants; and

the collaboration has little impact on the ability of businesses outside the group to compete.

If an authorisation has a significant anti-competitive element, the applying party or parties will need to demonstrate an even more significant public benefit, so as to outweigh the detriments. If there is a net public benefit, the ACCC may be willing to grant authorisation despite a detrimental impact on competition.

Some specific examples of sustainability collaborations for which the ACCC has granted authorisations are set out in the table below:

| Types | Examples |

| Industry stewardship arrangements which impose a levy on the sale of products to increase the level of recycling or safe disposal of potentially harmful end-of-life products (such as batteries, paint, tyres and soft plastics). | On 4 September 2020, the ACCC granted conditional 5-year authorisation to the Battery Stewardship Council for a Battery Stewardship Scheme (BSS). The BSS applies a levy of $0.04 per 24 grams on imported batteries. Funds generated go towards the BSS itself and a rebate system for those providers managing battery collection, sorting, and processing. On 26 October 2022, the ACCC granted a conditional 5-year authorisation to the Australian Bedding Stewardship Council Limited for the ‘Recycle My Mattress’ scheme, which focuses on resource recovery and stopping mattresses from ending up in landfill. |

| Joint tendering by local councils, who by combining their volumes can underwrite investment in a new waste recycling processing facility and promote environmental benefits such as diversion of waste from landfill, increased generation of renewable energy from waste and decreased greenhouse gas emissions. | On 23 March 2022, the ACCC granted authorisation for 9 years and 6 months to Barwon South West Waste and Resource Recovery Group and six local councils, which sought to engage in joint tendering for e-waste services. On 31 January 2024, the ACCC granted authorisation for 27 years to Hunter Resource Recovery and several councils to jointly procure, through a tender process, and contract for the establishment of a recycling processing and sorting facility |

| Joint buying groups to purchase renewable energy, resulting in reduced greenhouse gas emissions by enabling members of the buying group to transition to renewables at lower cost and with less risk than if they each sourced renewable energy individually | On 26 August 2021, the ACCC granted a 12 year and 6-month authorisation to the Barwon Region Water Corporation, Barwon Health and Geelong Port Pty Ltd, which sought to create the Barwon Regional Renewable Energy Project, a joint renewable energy purchasing group to source electricity from a generator of renewable energy. On 29 March 2023, the ACCC granted authorisation for 11 years to the current and future organisations forming the Business Renewables Buying Group, which seeks to pool electricity demand and negotiate to ensure supply from a renewable energy project or projects connected to the National Electricity Market. |

| Major supermarkets collaborating to manage disruptions to in-store collections of soft plastics for recycling. | On 30 June 2023, the ACCC granted a conditional 1-year authorisation to Coles Group Limited, Woolworths Group Limited and ALDI Stores, which sought to form the Soft Plastics Taskforce and implement recycling initiatives for soft plastics following the suspension of the REDcycle program. |

Types

Examples

On 4 September 2020, the ACCC granted conditional 5-year authorisation to the Battery Stewardship Council for a Battery Stewardship Scheme (BSS). The BSS applies a levy of $0.04 per 24 grams on imported batteries. Funds generated go towards the BSS itself and a rebate system for those providers managing battery collection, sorting, and processing.

On 26 October 2022, the ACCC granted a conditional 5-year authorisation to the Australian Bedding Stewardship Council Limited for the ‘Recycle My Mattress’ scheme, which focuses on resource recovery and stopping mattresses from ending up in landfill.

On 23 March 2022, the ACCC granted authorisation for 9 years and 6 months to Barwon South West Waste and Resource Recovery Group and six local councils, which sought to engage in joint tendering for e-waste services.

On 31 January 2024, the ACCC granted authorisation for 27 years to Hunter Resource Recovery and several councils to jointly procure, through a tender process, and contract for the establishment of a recycling processing and sorting facility

On 26 August 2021, the ACCC granted a 12 year and 6-month authorisation to the Barwon Region Water Corporation, Barwon Health and Geelong Port Pty Ltd, which sought to create the Barwon Regional Renewable Energy Project, a joint renewable energy purchasing group to source electricity from a generator of renewable energy.

On 29 March 2023, the ACCC granted authorisation for 11 years to the current and future organisations forming the Business Renewables Buying Group, which seeks to pool electricity demand and negotiate to ensure supply from a renewable energy project or projects connected to the National Electricity Market.

Some other case studies of conduct that the ACCC may authorise which have been included in the Draft Guide are as follows:

agreeing to only acquire from suppliers who meet environmental standards;

agreeing not to use plastic wrap on products;

joint development of technology with environmental benefits;

sharing of information and agreeing not to deal with certain suppliers or acquirers to improve recycling rates; and

sharing of information and coordination activities to reduce food waste.

Timeframes

There is scope to seek interim authorisations pending the ACCC’s consideration of a substantive authorisation application. In considering whether to grant interim authorisation, the ACCC will take into account matters including:

the extent to which the relevant market will change if the interim is granted; and

the urgency and possible harm to the applicant(s) if interim authorisation is denied.

The ACCC must make a determination in relation to an application for authorisation within 6 months. Before doing so, it must issue a draft determination and undertake a public consultation process. That said, in some circumstances, the ACCC may consider streamlining the process, potentially allowing for authorisation to be granted more quickly, including where:

there do not appear to be any significant detriments associated with the conduct; and

the application deals with a subject matter or industry that the ACCC has previous experience with and has concluded there was a clear net public benefit for similar arrangements.

Next steps

The ACCC is seeking feedback from businesses, peak bodies, and other stakeholders on the Draft Guide, by 26 July 2024.

The ACCC will then consider submissions and anticipates publishing a finalised guide in late 2024.

This guide will be an important framework moving forward for how businesses collaborate in reducing the adverse impacts of economic activities on the environment and pursuing positive sustainability outcomes.

Businesses should closely follow the consultation process and keep abreast of the issues being raised by industry and key stakeholders. We will publish a further article once the final Guide is released, detailing any amendments from the Draft Guide and the implications for businesses.