This article forms part of our ongoing reporting on the merger reforms. For the most comprehensive and up-to-date analysis, please click here.

What we’re trying to capture – and really what that translates to is what we’re trying to see – are private equity serial acquisitions and roll-ups.

The significance of the ACCC’s merger reforms was already well known to private equity (you can find a snapshot of the key changes and practical implications of the merger reforms here). However, in an 25 October interview with the Australian Financial Review and then in a speech on 11 November, the ACCC and government have respectively called out private equity bolt-ons and roll-ups as an area of focus.

First, ACCC Chair, Gina Cass-Gottlieb, signposted which industries the ACCC will be scrutinising particularly closely, being liquor, pathology and private cancer radiation chains. Then the Assistant Minister for Competition, Andrew Leigh, said new data analytics tools are combining with existing databases to show that serial acquisitions in childcare, aged care, medical GPs and dentists are creating “competition hotspots”.

With the merger law reform Treasury Laws Amendment (Mergers and Acquisitions Reform) Bill 2024 (the Bill) in parliament and now with the official support of both parties, it’s an opportune time for private equity to take stock on investment and exit strategies for the interim period between now and 1 January 2026 when the new laws take effect, and then for the period beyond.

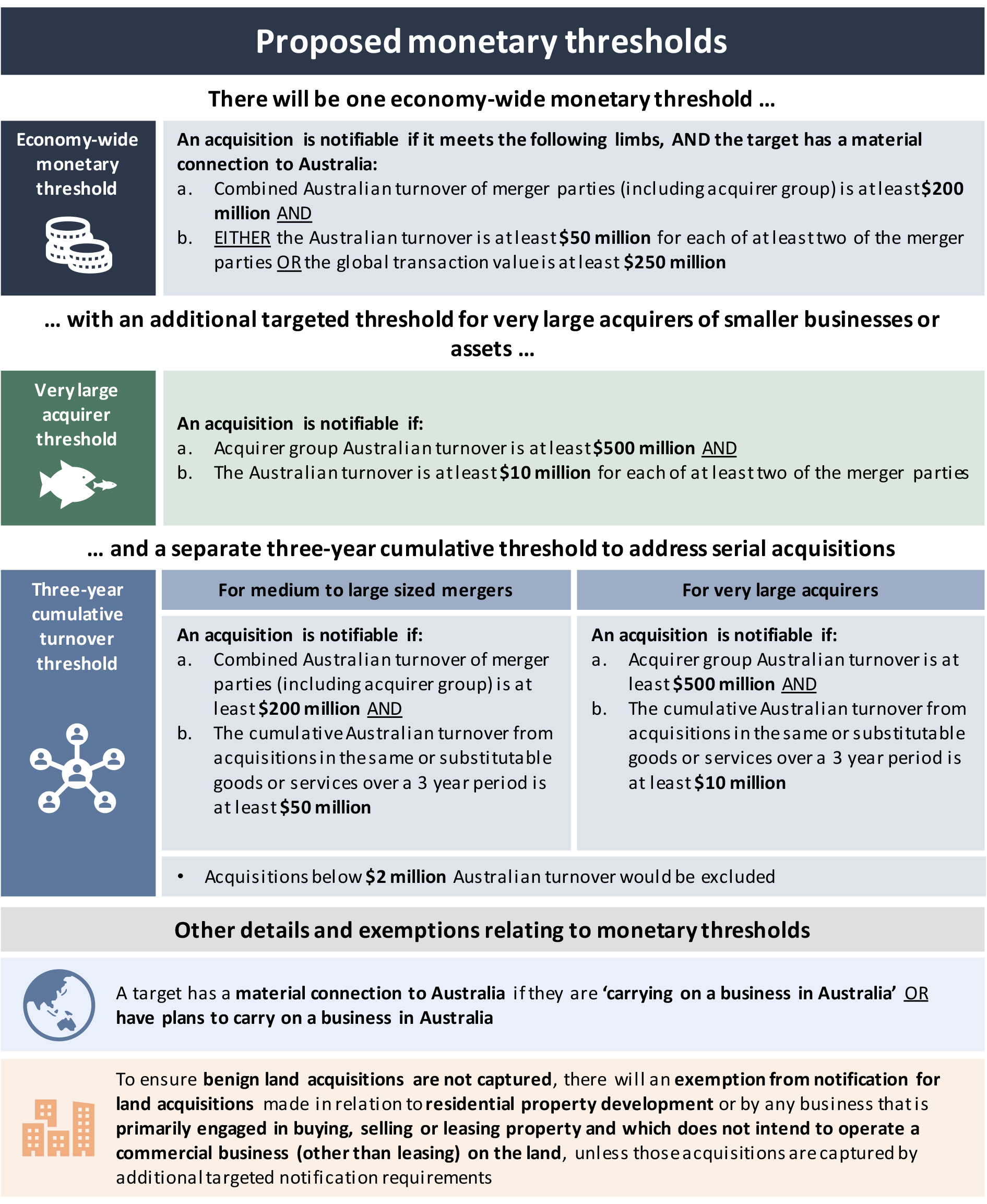

Treasury has also publicly released the initial merger notification thresholds which further underscore the increased focus on bolt-ons and roll ups. It also increases the likelihood of global transactions being captured by mandatory filing requirements where a private equity fund has a local Australian presence and revenues – given the thresholds are captured where there is a ‘material connection to Australia’ (a concept which is not yet defined).

We provide some practical tips for private equity firms and their management teams below.

Planning for between now and 1 January 2026

Between now and 1 January 2026, the existing voluntary regime will continue to apply.

This means that absent a requirement to seek approval from FIRB, private equity firms still have the option of deciding whether to notify the ACCC or not. This is the case for any initial investment into an industry or any bolt-ons. The transitional provisions in the Bill mean that where clearance is obtained before 31 December 2025, the merger parties have 12 months to complete the transaction without the need to refile under the mandatory regime.

As a reminder, the ACCC’s 2008 Merger Guidelines provide the current informal ‘threshold’ for voluntary notification:

Merger parties are encouraged to notify the ACCC well in advance of completing a merger where both of the following apply:

the products of the merger parties are either substitutes or complements; and

the merged firm will have a post-merger market share of greater than 20 per cent in the relevant market/s.

When the government introduced the Bill to parliament on 10 October, it also released its response to the consultation it had conducted. That response contained a helpful diagram of the three new thresholds that will take effect on 1 January 2026. This diagram is reproduced at the end of this article.

Private equity firms looking at a pipeline of Australian deals should take advice about timing and the potential benefits of closing deals prior to the end of 2025.

Significance to private equity of the ‘Three-year cumulative turnover threshold’

For private equity, one particularly important threshold is the ‘Three-year cumulative turnover threshold’ which requires mergers to be notified when:

The combined Australian turnover of merger parties (including acquirer group) is at least $200 million.

The cumulative Australian turnover from acquisitions in the same or substitutable goods or services over a three-year period is at least $50 million.

The target has greater than $2 million in Australian turnover.

OR

Combined Australian turnover of merger parties (including acquirer group) is at least $500 million.

The cumulative Australian turnover from acquisitions in the same or substitutable goods or services over a three year period is at least $10 million.

Target has greater than $2 million in Australian turnover.

The three-year look-back period is relevant both at the notification phase (for example in determining whether an acquisition needs to be notified) as well as the substantive consideration by the ACCC of the competitive effects of a transaction. This is because the ACCC may treat the effect of an acquisition as being the combined effect of:

(a) the current acquisition; and

(b) any one or more acquisitions:

That are put into effect during the three years ending on the date the notification is officially received by the ACCC.

The parties to which include any party to the current acquisition or, if a party to the current acquisition is a body corporate, include a body corporate that is related to that party.

The targets of which are involved (directly or indirectly) in the supply or acquisition of the same goods or services or goods or services that are substitutable for, or otherwise competitive with, each other (disregarding any geographical factors or limitations).

Why is the three-year look back significant for private equity?

There are a number of reasons:

Three years has already started: even though the voluntary notification regime remains in place until 1 January 2026, the three year look back period should be treated as having already started. This means any acquisition involving the same or substitutable goods or services from 1 January 2023 will be relevant to determining notification requirements and the ACCC’s assessment of the effect of any future bolt-ons (regardless of where the acquisition occurred).

Changes to RFIs in standard due diligence: private equity firms (and others) on the buy-side should now be making it a standard part of their due diligence to place RFIs asking the vendor to:

Identify any completed transactions for substitutable goods or services over the past three years.

Explain whether it did notify or seek clearance from the ACCC and, if not, why not.

The purpose of these RFIs for the bidder is to get a better sense of:

When you may be required to notify the ACCC because of the three-year cumulative turnover threshold – it may be that the first bolt-on you do crosses the threshold.

How the ACCC may view the competitive effects of the cumulative deals. The case in point is Woolworths’ acquisition of a controlling interest in Petstock, where the ACCC was less concerned about Woolworths’ investment and more concerned about the various acquisitions that Petstock had already completed without notifying the ACCC. As a condition of clearing the deal, the ACCC required Petstock to divest 41 specialty pet retail stores, 25 co-located veterinary hospitals, four brands and two online retail stores.

Growth and exit strategy considerations: following on from the above, when considering exit strategies as a vendor, private equity firms and their management teams should be contemplating how potential bidders may view decisions on whether to notify the ACCC or not. While it will not necessarily cause bidder concern if as a vendor you have done deals without notifying the ACCC, vendors should anticipate that bidders will place the RFIs noted above.

A more costly and complex process

As well as the threshold and look-back period, the new regime also introduces changes to the substantive merger clearance test that will make bolt-on transactions more complex and challenging in concentrated markets.

The Bill introduces new language that reinforces the ability of the ACCC to block deals that “create, strengthen or entrench” a position of substantial market power. This is squarely focused on giving the ACCC stronger tools to prevent incremental bolt-on transactions in concentrated markets.

The regime is also likely to introduce substantial new application fees and a greater emphasis on up front evidence and costly economic data and analysis. Application fees are likely to be $50,000-$100,000 for significant transactions.

More detail around the ACCC’s intended process, application requirements and filing fees will be released over the next six months.

Important transitional arrangements

In continuing to plan growth strategies, the following transitional timeline can assist private equity firms with planning.

Date | Event | |

Now until 31 December 2025 | Merger parties can continue to voluntarily engage with the ACCC under the current informal merger clearance process. | |

30 June 2025 | The final date by which merger authorisation applications must be made to the ACCC. | |

1 July 2025 | Merger parties will be permitted to voluntarily notify and opt into the new mandatory and suspensory system. | |

1 July and 31 December 2025 | Businesses that have received informal ‘clearance’ or been granted merger authorisation under the current system between 1 July 2025 and 31 December 2025 will be exempt from notification, provided the acquisition is put into effect within one year. | |

1 January 2026 | Businesses must notify the ACCC of notifiable acquisitions. |

Factors to consider from 1 January 2026

Once the new regime commences there will be some important factors for private equity firms to consider:

Timing for clearance: the ACCC also released a statement of goals in which it assures businesses it expects to make a determination in 15 to 20 business days for around 80% of mergers, either through an early Phase 1 determination or the new notification waiver process (which the ACCC supports – see below).

Waivers: following calls from business and other stakeholders, the Bill allows merger parties to request that the ACCC waive the obligation to notify an acquisition. In deciding whether to grant a waiver, the ACCC must have regard to a number of factors including the likelihood that the acquisition would, if put into effect, have the effect of substantially lessening competition. The ACCC has said that it is keen to ensure the waiver system works effectively by it granting waivers within a very short period of time, but it has also said that its effective operation will require parties to provide ‘sufficient information’.

ACCC sensitive industries: the new regime introduces a Ministerial power to impose targeted notification thresholds for certain mergers. The government intends to require every merger in the supermarket sector to be notified to the ACCC. Further, in her October interview with the AFR, Gina Cass-Gottlieb said once the laws were passed through parliament she would ask Treasurer Jim Chalmers to designate the liquor, pathology and oncology-radiology sectors as well.

Greater scrutiny of cross-shareholdings and cross directorships: globally, competition law regulators have been increasing their scrutiny of private equity cross-shareholding and cross-directorates or interlocking directorates. For example, interlocking directorates are mostly banned by section 8 of the Clayton Act in the US, and in Europe regulators have been using merger control provisions and processes to prevent these outcomes. As the ACCC has specifically called out private equity roll-ups as a focus of the new regime, PE firms in Australia should anticipate receiving more questions about cross-shareholdings and interlocking directorates even when different funds are involved.

A new level playing field: to date, private equity firms that have required FIRB approval for transactions may have found themselves at a competitive disadvantage to other bidders in a tender process because they needed to include a FIRB condition precedent (CP). Further, needing FIRB approval also meant the need to consider an ACCC strategy as a result. Under the new regime, the playing field will become more level as any bidder who crosses the ACCC notification thresholds will need to engage with the ACCC.

Competitive disadvantage turned advantage for prior FIRB and ACCC approvals: private equity firms that were required to seek FIRB approval for prior deals will also have the benefit of knowing that the ACCC has seen these deals and was comfortable with them. This means on exit the new owner won’t be confronted with a Petstock divestiture situation.

What ACCC CP will you use?:

Where notification is required, what ACCC CP will you use? Negative, positive or none?

How much ACCC risk are you prepared to take on in a competitive tender process?

If you have a complex deal in the first half of 2025 (for example before voluntary filing is available) you will need to consider addressing any risks that might arise if clearance is not obtained by the end of 2025.

Confidentiality:

Under the new regime, all notified acquisitions will be published on an ACCC public register. The only and narrow exception included in the Bill is for surprise hostile takeovers and, even then, the exception is limited.

At this stage, it is unclear exactly what will be required to be published on the public register, including the original application form. The contents of the register will be prescribed later by a legislative instrument which is expected to be released for consultation early in 2025.

Thoughts on next steps

With the benefit of greater clarity on the merger notification thresholds, as well as the ACCC’s enforcement position, private equity firms can now plan and refine their growth strategies with more certainty.

While private equity is in the ACCC’s focus, the change in merger clearance regime should not deter private equity firms from seeking the same growth as they have to date. This can be done with a well-considered ACCC strategy.